Introduction: The Myth of the Fourth Estate in an Era of Democratic Backsliding

In Smethurst v Commissioner of Police, the High Court of Australia exposed a fragility at the heart of the modern democratic constitution. The case revealed a flaw in the assumption that a “free press”—an independent media unrestrained by government interference—operates as a reliable counterweight to executive power. After federal agents raided the home of a political journalist, the Court held the warrant invalid on technical grounds but refused to order the return of the seized data. As a result, the state remained in possession of the fruits of its unlawful conduct.

This judicial paradox shows a systemic problem: the transformation of the Fourth Estate (the press acting as a societal watchdog) from an accountability check into a site of what Lawrence Lessig calls ‘dependence corruption’—corruption that arises when institutions become reliant on influences that undermine their independence. This article argues that ‘media capture’—systemic control or undue influence over the media—is not only a symptom of authoritarian backsliding in places like Turkey or Hungary. It is also an advanced feature of established democracies, maintained through legal formalism and economic strangulation.

Once, belief in the media as an independent check on government corruption was underpinned by professional integrity and truth; now, after recent global political developments, such belief is increasingly untenable. Previously, the Fourth Estate served as a constitutional counterweight to government power. Today, it seems as illusory as fictional characters in political dramas, which normalise this ideal through constant cultural repetition. This rising disillusionment reveals not only failures in journalistic ethics but also a deeper systemic problem: media institutions have shifted from mechanisms of accountability to instruments of “dependence corruption”.

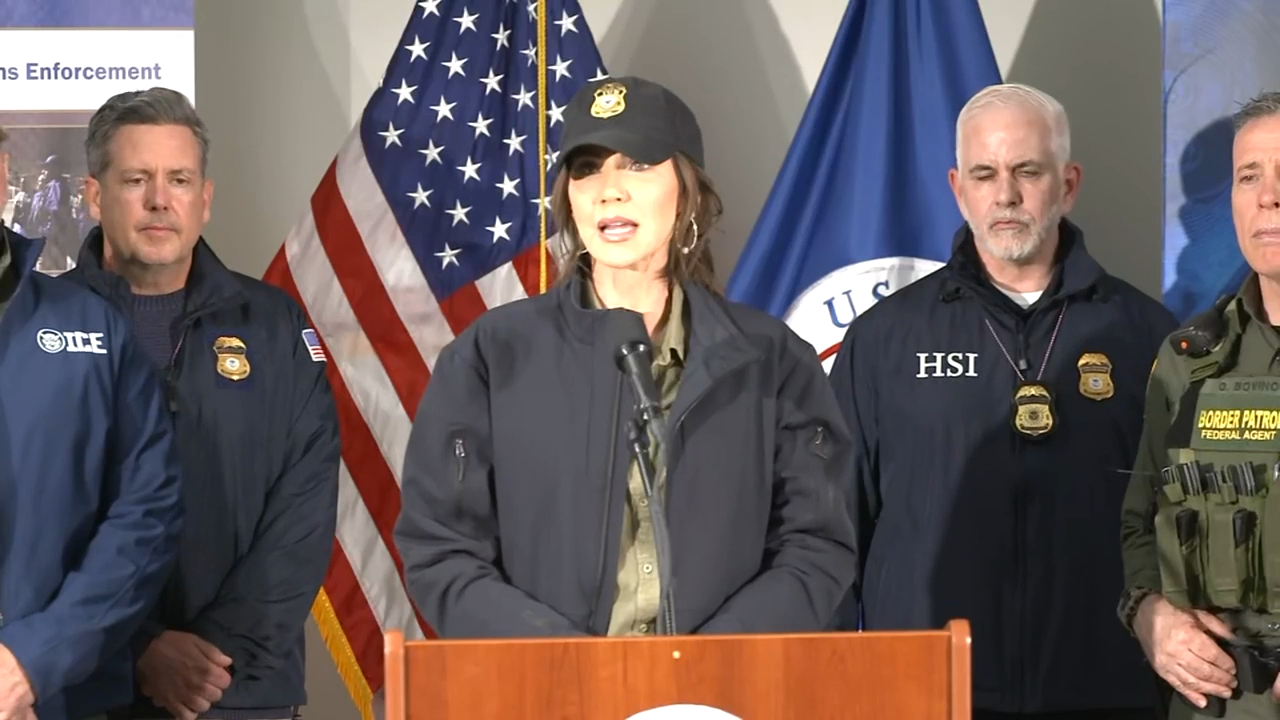

Press independence today rarely erodes through overt censorship or direct authoritarian control. Instead, democratic backsliding tends to erode institutional autonomy bit by bit. Media freedom worsens alongside other democratic indicators in a self-reinforcing cycle. The V-Dem Institute’s 2025 Democracy Report shows that 45 countries are now experiencing ‘autocratization’, while freedom of expression is declining in 44—the highest on record. This regression spans beyond fragile states. In the United States, journalist Mario Guevara’s 2024 detention under immigration statutes shows how administrative law can silence critical reporting. Unlike Turkey’s open use of criminal defamation, this ‘administrative capture’ gives the state a legal façade, yet still silences dissent.

This article presents three main arguments. First, media capture is a form of institutional corruption that advances governmental and corporate interests while reducing public accountability—often without breaking the law. Robust oversight bodies and transparent funding audits can help address this. Second, the mechanisms of capture—access journalism, economic dependencies, regulatory manipulation, and cognitive socialisation—form a self-sustaining system that marginalises independent journalism and lends credibility to captured outlets. Stringent antitrust regulations and independent regulatory checks can counteract these patterns. Third, social conditioning sustains the illusion of press freedom. As a result, citizens are inclined to accept governmental transparency and institutional benevolence, dismissing evidence of corruption until those beliefs become untenable. Media literacy and public awareness campaigns can reduce this illusion and help citizens challenge media capture.

I. Theoretical Frameworks: Institutional Corruption and Media Capture

A. Institutional Corruption as Systemic Pathology

Institutional corruption theory, pioneered by Dennis Thompson and developed by Lawrence Lessig, offers essential analytical tools for understanding media–government symbiosis as something more pernicious than isolated ethical lapses. This framework distinguishes between conventional corruption—individual acts of bribery or embezzlement that contravene established norms—and institutional corruption, in which systemic arrangements cause institutions to deviate from their proper purposes without necessarily involving illegality.

The Thompson–Lessig model conceptualises institutional corruption as an “economy of influence” that weakens both institutional effectiveness and public trust. Applied to the media, this framework illuminates how structural dependencies generate what Lessig terms “improper dependencies,” diverting press institutions from their democratic role. Corruption here does not depend on journalists accepting bribes; it arises from collective arrangements. Media organisations may become dependent on government access, advertising revenue, and regulatory favour, thereby advancing governmental and corporate interests over the public interest. For example, a local newsroom operating on a tight budget may trade editorial independence for reliable government advertising subsidies. Over time, this financial reliance nudges coverage away from critical reporting, transforming an independent watchdog into a compliant outlet. This scenario brings Lessig’s point into focus, as the publication is forced to weigh economic survival against its journalistic mission.

The mechanics of this capture are increasingly well understood. As of late 2025, the Medill School reports that 213 U.S. counties are “news deserts” with no local outlets, and another 1,524 counties have only a single source, creating information monopolies. This is not mere market failure; it is structural capture. “Ghost newspapers” retain their mastheads but have lost more than half their reporting staff, often repackaging press releases as news.

Institutional corruption can occur without intentional norm violations, making it particularly insidious for rule-of-law frameworks. Conventional anti-corruption enforcement satisfies the rule-of-law requirements of transparency and predictability by identifying clear violations of individual conduct norms. Institutional corruption, by contrast, indicts entire political systems for normalising illegitimate self-interest within political discourse. Even while operating within legal boundaries, it can profoundly undermine rule-of-law principles.

B. Media Capture Theory and Democratic Degradation

Media capture theory, developed by Besley and Prat and later extended, models how interest groups and governments manipulate the media. This affects electoral outcomes and policy decisions. The theory predicts that capture probability increases with media industry concentration, ownership structure, and the proportion of revenue from government sources. When media plurality is low, governments can more easily bribe or coerce the industry. High wealth concentration lets owners gain disproportionate benefits by manipulating public opinion.

Empirical research shows that autocratic regimes prioritise state capture of media. Free media exposes corruption and informs the public, threatening captor networks. Captor elites respond by manipulating broadcast licenses, withdrawing government advertising from noncompliant outlets, intimidating journalists, and awarding contracts for favourable coverage. These methods create what scholars call “cognitive capture,” where journalists internalise regime preferences without direct coercion.

The V-Dem Institute’s Media Capture Index quantifies this phenomenon, showing that declines in media integrity correlate strongly with democratic backsliding across regions. In countries experiencing autocratization, media freedom is attacked first and most aggressively, creating a permissive environment for dismantling other democratic institutions. The mechanism operates through both direct censorship and more subtle forms of control: captured ownership, regulatory burdens, biased judiciary enforcement, and financial incentives that gradually erode genuine independence.

C. The Rule of Law and Press Freedom as Institutional Prerequisites

The rule of law requires not just formal legal provisions but functional institutional mechanisms that limit arbitrary power and ensure governmental accountability. Press freedom is a vital pillar of this framework, enabling public oversight of government power. However, constitutional protections vary significantly across jurisdictions, with significant implications for democratic resilience. What moral justification underpins the special status afforded to the press? This question invites readers to reflect on the deeper democratic values that elevate the legal consideration of press freedom beyond mere doctrinal concerns.

Comparative analysis reveals stark differences. The United States First Amendment provides categorical protection: “Congress shall make no law... abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press”. South Africa’s Constitution explicitly enumerates “freedom of the press and other media” as a distinct right within freedom of expression. By contrast, Australia’s constitutional system provides only an implied freedom of political communication, which the High Court has found within the text but which offers much weaker protection. The United Kingdom relies on statutory and common law safeguards, while Canada provides explicit Charter protection for press freedom. To navigate these varied landscapes and promote press freedom, policymakers might use constitutional levers, such as antitrust caps on media ownership to prevent excessive concentration, establishing public trusts to support independent journalism, and enacting transparency laws regarding media funding. These instruments help strengthen media diversity and resist capture, maintaining a robust democratic ecosystem.

These variations matter because captured media environments can enable rule-of-law degradation through multiple pathways. When media independence erodes, corruption increases, judicial independence weakens, and human rights protection deteriorates. In Guatemala, captured judiciary and prosecutorial institutions have been used to prosecute anti-corruption activists, granting elites total impunity. In Hungary and Poland, media capture came before and enabled broader democratic backsliding by silencing critical voices and manipulating public discourse.

II. The Mechanisms of Media-Government Symbiosis

A. Access Journalism and Information Cartels

The relationship between government and mainstream media often functions as a carefully maintained symbiosis. It reduces the likelihood of unfavourable coverage while ensuring that select outlets receive exclusive access, advance notice of policy, and privileged insights. This dynamic creates an information cartel in which insider status becomes more valuable than investigative rigour. Despite these structural pressures, some publications have chosen to sacrifice government access in exchange for the transformative potential of adversarial reporting. The Guardian’s decision to prioritise the Snowden revelations over preserving governmental relationships, for example, illustrates the substantial societal impact of such journalism. This contrast highlights the stakes: short-term gains from access versus the long-term value of genuine investigative work.

Access journalism can transform media organisations from watchdogs into stenographers, dependent on official sources for scoops that drive ratings and advertising revenue. Competitive advantage accrues not to outlets with exceptional investigative capacity but to those that maintain favourable relationships with power. This arrangement rewards professional recklessness: the benefits of rapid publication are immediate, while the verification of purported truths is postponed. As Jonathan Swift observed, “Falsehood flies, and truth comes limping after it,” so that the jest is complete before the deception is exposed.

This mechanism operates through subtle exclusion. Outlets that pursue accountability journalism find their access curtailed, their sources drying up, and themselves cast as fringe or biased. Meanwhile, captured media gain a competitive edge and prestige through collusion with corrupt interests, often with impunity. This dynamic creates an illusion of superior journalistic expertise, leading the public to assume that elevated stature reflects investigative rigour rather than institutional co-option.

B. Economic Capture Through Advertising and Ownership

Media capture theory identifies economic dependencies as primary vulnerabilities. Governments control substantial advertising budgets that media organisations rely on for revenue, creating leverage to discipline critical coverage. In Turkey, the AKP government systematically withdrew advertising from opposition outlets while directing resources to friendly media. This led to financial starvation of independent journalism, with reports indicating that up to 70 per cent of government advertising was redirected to supportive outlets. Similar patterns appear across other cases of democratic backsliding, where “advertising capture” supplements ownership concentration.

Ownership structure further determines susceptibility to capture. When wealthy conglomerates control media outlets, their interests often diverge from those of the median voter, creating incentives to manipulate electoral outcomes through biased reporting. The Besley–Prat model shows that wealth concentration increases the probability of capture because the largest shareholders disproportionately benefit from profitability increases induced by favourable regulation. This dynamic helps explain why media concentration correlates with higher corruption levels and longer political leader tenure.

Digital transformation has deepened these vulnerabilities. As advertising revenue has shifted to social media platforms and the traditional journalism business model has collapsed, media outlets have become increasingly dependent on government subsidies and wealthy patrons. Over the past two decades, newsroom closures and journalist layoffs have created “news deserts” where local politicians, courts, and businesses operate with little or no scrutiny. As local newspapers close, corporate pollution increases, voter turnout declines, and political partisanship intensifies.

C. Cognitive Capture and Professional Socialisation

Most insidiously, capture operates through cognitive mechanisms that reshape journalistic norms and practices from within. Cognitive capture theory suggests that ideology becomes woven into journalists’ thinking and routines, generating self-censorship and institutional quiet even in the absence of explicit threats. This often manifests as “issue avoidance,” whereby media organisations collectively refrain from investigating governmental overreach, corruption, or abuse. Journalism schools may unwittingly reinforce these dynamics. Systematically examining potential biases in curricula and pedagogical practices could yield more profound insights into how professional training contributes to the internalisation of norms. Such an inquiry highlights a reform lever frequently overlooked in debates about safeguarding press independence.

The contrast between institutional quiet and independent courage is particularly damaging. When mainstream outlets ignore whistleblower cases or instances of governmental overreach, they implicitly frame these stories as fringe concerns. Independent reporters, lacking institutional backing, shoulder the burden of accountability journalism while facing accusations of bias or sensationalism. This dynamic erodes public trust in alternative perspectives and entrenches preferred governmental narratives.

Professional socialisation further compounds these effects. The capacity of influential outlets to recruit the most talented journalists helps perpetuate the illusion of integrity, as corrupt money purchases public trust through opulence, prestige, and panache. The process appears self-evident yet often escapes scrutiny, because social conditioning predisposes citizens to assume that governmental systems are essentially transparent and benevolent. This cognitive bias makes populations dismissive of damning revelations until disbelief becomes impossible to sustain.

D. Legal and Regulatory Capture

Media capture extends into legal and regulatory frameworks that nominally protect press freedom but are manipulated to serve governmental interests. Governments deploy defamation laws, national security legislation, and regulatory bureaucracy to harass journalists and outlets. Australia’s counter-terrorism laws, for instance, criminalise a wide range of political expression without requiring proof of harm, undermining press freedom despite an implied constitutional freedom of political communication. Notably, there has been a marked global rise in Strategic Lawsuits Against Public Participation (SLAPPs)—cases designed less to succeed on the merits than to burden opponents with legal costs and deter them from exercising their free speech rights. This trend demonstrates how informal pressure can effectively suppress scrutiny, deepening the chilling effect on investigative journalism.

In Turkey, regulatory capture has proved decisive. The AKP government warped legal frameworks to take over the media through manipulated tenders and confiscations, particularly after the 2001 economic crisis. Media outlets that had actively criticised the government were targeted by the Banking Regulation and Supervision Agency and the Savings Deposit Insurance Fund, which seized their assets and transferred them to government-aligned owners. This process created a hybrid media system oscillating between relative freedom and near-total control, progressively shifting toward illiberalism through capture mechanisms.

Constitutional protections prove insufficient without robust statutory implementation. While the United States provides categorical First Amendment protection, recent developments show that even strong constitutional provisions can be undermined through regulatory harassment, lawsuits, and funding threats. The Trump administration’s exclusion of critical media from White House events, lawsuits against outlets, and threats to rescind broadcast licences illustrate how legal formalism can be circumvented through informal pressure.

III. Empirical Evidence of Systemic Media Capture

A. Comparative Analysis: Turkey, Hungary, and Poland

Turkey represents the most dramatic contemporary example of media system capture. Over two decades, the AKP government transformed a pluralist, polarised media system into a captured environment through confiscation, manipulated tenders, and financial sanctions. By 2023, Turkish media exhibited dictatorial levels of control, with intimidation tactics ranging from regulatory harassment to imprisonment of journalists. V-Dem data shows rapid declines across multiple indicators: government censorship, media self-censorship, journalist harassment, and dissemination of false information.

Hungary and Poland demonstrate how media capture within the European Union facilitates democratic backsliding. In Hungary, the Orbán government created a “media empire” through friendly ownership concentration, regulatory manipulation, and distribution of state advertising. The 2010 media law enabled partisan appointment of media regulators, while constant “media reform” created uncertainty that favoured government-aligned outlets. Poland’s PiS regime similarly installed party loyalists as CEOs and senior executives of public media companies after the 2016 legal changes, while using licensing powers and the allocation of advertising to discipline private outlets.

These cases exhibit a typical sequence: media capture frequently precedes and enables broader democratic erosion by silencing critical voices, manipulating public discourse, and weakening institutional checks on executive power. Initially, capture occurs through ownership concentration and dependence on government advertising, which diminishes public scrutiny and reshapes media narratives. This, in turn, contributes to weakened judicial autonomy, as courts face less exposure and pressure from an informed public. Judicial weakening then facilitates policy shifts that favour entrenched elites, revealing a transparent causal chain from media capture to systemic democratic backsliding. Correspondingly, the V-Dem Media Capture Index shows that these countries recorded some of the most significant global declines in media integrity between 2012 and 2017.

B. Subtle Erosion: Australia, the United Kingdom, and the United States

Media capture operates through more subtle mechanisms in established democracies, making it potentially more dangerous because it maintains a democratic façade while hollowing out accountability functions. Australia’s constitutional system provides only an implied freedom of political communication, leaving press freedom vulnerable to national security legislation and counter-terrorism laws that criminalise public-interest journalism. Federal Court decisions confirm that legal protections for independent media remain sorely lacking.

This erosion is most acute at the local level, where the collapse of the business model has created a vacuum filled by ‘ghost newspapers’. According to Medill’s 2025 data, over 50 million Americans now live in counties with limited or no access to local news, a condition that correlates directly with reduced civic engagement and increased polarisation. These ‘ghost’ publications, stripped of investigative capacity, often serve as mere conduits for municipal press releases, effectively privatising the public record.

Conclusion: From Institutional Mirage to Democratic Reality

The analysis presented in this article leads to a sobering diagnosis: the Fourth Estate, as it currently operates in many liberal democracies, functions less as a bulwark against power than as a subtle instrument of its consolidation. Viewed through Lawrence Lessig’s framework of institutional corruption, this failure is not merely a series of ethical lapses or market accidents. Instead, it reflects a form of “dependence corruption,” in which the survival of media institutions has become contingent upon the very political and corporate structures they are meant to scrutinise. As illustrated by the judicial paradox in Smethurst, legal formalism alone—whether in the guise of the First Amendment or implied constitutional freedoms—is insufficient to protect the press once the underlying architecture of the media market has been captured.

The transition from this “institutional mirage” to a functioning accountability mechanism requires more than nostalgia for a golden age of reporting that likely never existed. It demands recognition that press freedom is a constructed achievement, not a natural state. The most insidious barrier to this reconstruction is the “cognitive capture” detailed in Section II.C—the socialised belief that access equates to authority and that institutional benevolence is the default. Overcoming this requires a strategy of sustained political mobilisation operating on three fronts to dismantle the “economy of influence”.

First, mobilisation must target the depoliticisation of media economics. We must move beyond the binary of “state-controlled” versus “market-censored” media. Reforms should prioritise the creation of blind public trusts and portable journalist subsidies—mechanisms that provide financial oxygen to independent outlets without generating new dependencies on government favour. This, in turn, requires robust antitrust enforcement not only to punish monopolies but to dismantle the information cartels that trade access for compliance. Mobilisation here means treating media ownership concentration not as a business entitlement but as a democratic liability.

Second, we must disrupt the prestige of access journalism. The cultural valorisation of “insider” reporting must be challenged by a counter-narrative that privileges friction over proximity. Professional bodies, journalism schools, and civil society organisations must redefine the metrics of journalistic success, elevating adversarial investigative work over the passive receipt of authorised leaks. This is a project of cognitive decoupling: training both the public and the profession to view the “exclusive scoop” sourced from government with scepticism rather than reverence.

Finally, legal advocacy must shift from defensive reaction to offensive entrenchment. We cannot wait for another Smethurst to expose the hollowness of standard law protections. Mobilisation requires a concerted push for positive rights frameworks—statutory media freedom acts that codify protection for whistleblowers, shield sources from metadata retention regimes, and limit the executive’s capacity to use “national security” as a cloak for administrative capture.

The illusion of the Fourth Estate is comforting, but it is dangerous. It lulls citizens into a sound sleep while the infrastructure of accountability is quietly dismantled. Achieving a genuinely free press will not come from the benevolence of the state or the self-correction of the market. It will occur only when the preservation of an adversarial press is treated not as a niche professional concern, but as a central, non-negotiable demand of the democratic contract. The mirage has served its purpose; it is time to build the real thing.