The Structural Vulnerability: Pre-emptive Regulatory Powers and Their Exploitation

Victoria’s legal profession regulatory framework grants the VLSB extensive pre‑emptive powers to suspend practising certificates and intervene in law practices without first establishing misconduct.

This authority stems from the legal characterisation of lawyers as “officers of the Court,” whose ability to practise is treated as a privilege rather than a right. Under this framework, the regulator may take adverse action whenever the “public interest” allegedly requires it, even in the absence of conclusive evidence of wrongdoing.

While such powers may be intended for legitimate protective purposes, they have repeatedly been weaponised against small firms and sole practitioners—a pattern supported by numerous documented cases, including those of practitioners such as Peter Mericka and Sarah Tricarico. The targeted focus on vulnerable practitioners, coupled with a conspicuous lack of comparable action against large multinational firms, suggests a predatory regulatory strategy that leverages power imbalances rather than genuinely safeguarding the public.

The case of Sarah Tricarico starkly illustrates this concern. In 2025, the Victorian Supreme Court found the VLSB’s immediate suspension of her practising certificate to be “unreasonable” and “insufficiently cogent,” noting that she had received no prior notice and no opportunity to respond. Justice Peter Gray observed that the suspension was based solely on a charge sheet “unsupported by any statement or evidence of any kind,” with “no way of assessing whether there was a prospect the charge might in due course be proven.” This judicial rebuke exposes the recklessness inherent in unchecked pre‑emptive powers.

In 2009, the former Victorian Ombudsman, G. E. Brouwer, conducted an own‑motion investigation into the office of the Legal Services Commissioner following 95 complaints. Mr Brouwer found a systemic pattern of abuse of authority within those complaints.

A concise summary of the Brouwer Report, included in the Ombudsman’s annual report to the Victorian Parliament on 3 September 2009, stated:

“Over the past year, I received 95 complaints about the Legal Services Commissioner, which replaced the former Legal Ombudsman in December 2005. There were recurring themes in the complaints which pointed to a systemic failure by the Legal Services Commissioner to adequately undertake its statutory role. For example, complainants alleged that:

- complaints were inadequately investigated or not investigated at all

- there were significant delays – sometimes in excess of three years in finalising complaints

- documentation practices were poor and failed to provide complainants with information about the Legal Services Commissioner’s internal review process and external review mechanisms

- investigations lacked procedural fairness.

I also conducted an own motion investigation into the Legal Services Commissioner and its decision-making processes under section 14 of the Ombudsman Act because of the number of complaints I had received. My investigation identified a lack of understanding by staff of the Legal Services Commissioner’s statutory powers and a restricted skills-set to conduct investigations. The Legal Services Commissioner’s investigators showed limited knowledge of the basic techniques of investigative processes. Case files lacked:

- investigation plans

- thorough and professional approaches to gathering evidence

- follow-up on serious allegations

- substantiating documents such as practitioners’ files

- timely conclusions

- verification of practitioners’ responses

- reasons for decisions.”

“I made 28 recommendations to the Legal Services Commissioner and am pleased to note that it has taken steps to address a number of problems identified in my own motion investigation. I intend to review the Legal Services Commissioner’s implementation of my recommendations over the next year. I also referred the report of my investigation to the Attorney-General for his information, particularly in relation to the inability of the Legal Services Commissioner to re-open cases on the basis of merits.”

Unfortunately, the full report produced by Mr Brouwer (the Brouwer Report) following his investigation is not publicly available. The current Victorian Ombudsman, Ms Marlo Baragwanath, has successfully resisted disclosure of the Brouwer Report despite persistent efforts by many applicants to obtain it under the Freedom of Information Act 1982 (Vic).

This secrecy persists despite the continuing volume and seriousness of allegations against the VLSB since the publication of the Brouwer Report.

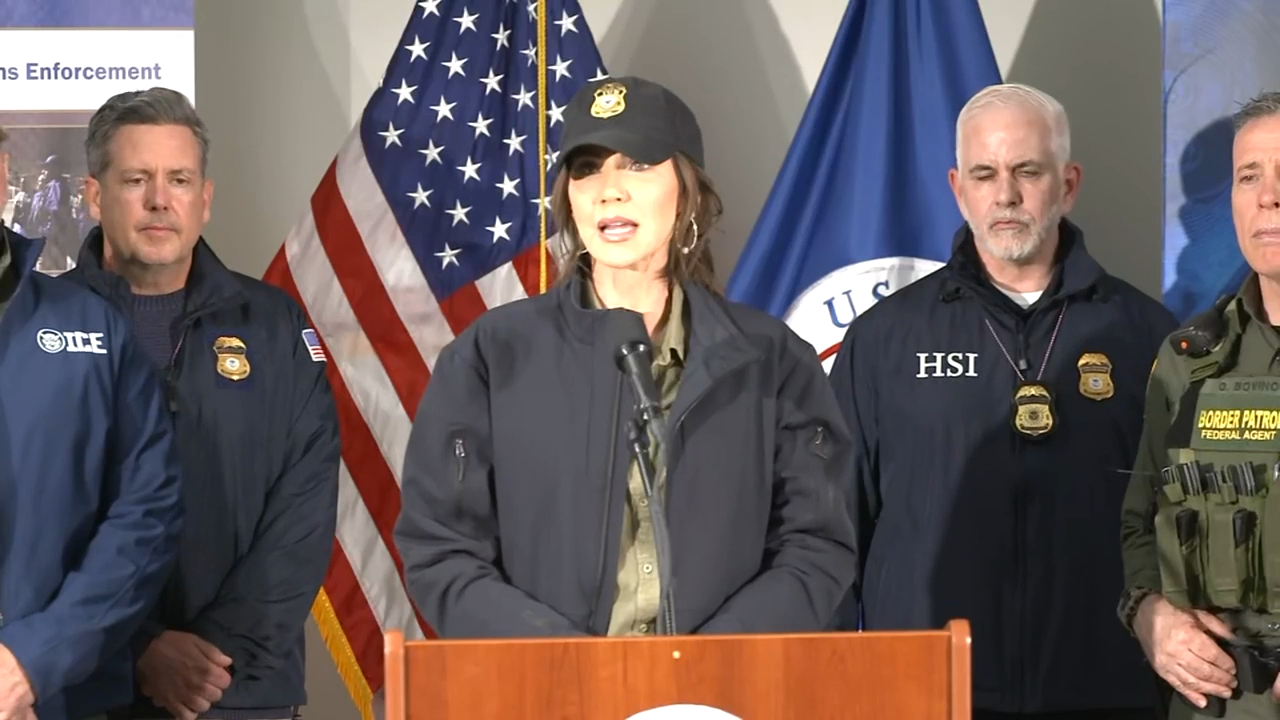

The VLSB consistently ranks at or near the top of the list of “regulators within the courts, legal and judicial sector” in terms of the number of misconduct and corruption complaints received each year by the Independent Broad-based Anti-corruption Commission (IBAC), and by a significant margin.

A snapshot of complaints received by IBAC for this sector in the financial year ending 30 June 2025 is provided below. These figures do not include complaints that IBAC rejects for lacking sufficient detail or for being otherwise inappropriate for its consideration.

IBAC’s own annually published statistics also consistently reveal a broad community view that:

- Corruption exists in Victoria and has a substantive impact on the performance of government functions; and

- The IBAC is ill-equipped to investigate, detect or prevent corruption or police misconduct.

The VLSB’s Google reviews present a striking catalogue of people from diverse backgrounds and experiences, seemingly united only by their desire to vent visceral frustration and anger at the regulator.

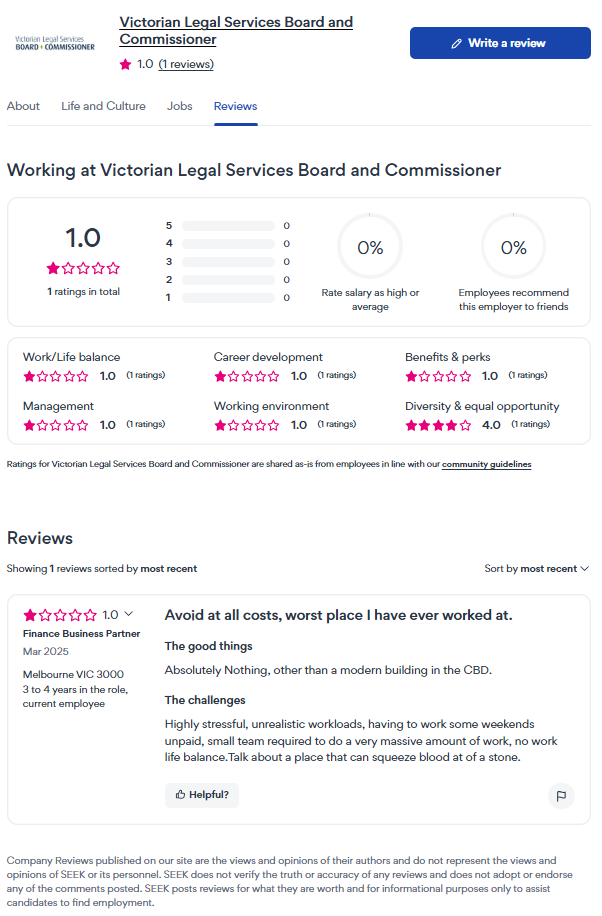

Unsurprisingly, the VLSB’s ignominy is not confined to condemnation by lawyers and consumers of legal services. Its own staff do not appear to be enthusiastic supporters either, as suggested by the sole review posted on the organisation’s recruitment platform of choice, Seek.

Seek’s policy for accepting employer reviews requires it to verify that all reviewers are genuine employees of the organisation they review.

The Folklore Effect: A Framework for Understanding Escalating Institutional Misconduct

We have developed a conceptual framework, the “Folklore Effect,” which synthesises insights from Prospect Theory, adverse selection principles, and Johann Graf Lambsdorff’s Institutional Economics of Corruption and Reform. The framework posits that once regulatory officials commit initial wrongdoing and become aware that evidence of their misconduct exists, they face escalating incentives to vilify and discredit the victim to prevent exposure.

Prospect Theory, developed by Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky, demonstrates that humans display loss aversion—valuing the avoidance of losses more than equivalent gains. Applied to corrupt officials facing potential exposure, this suggests they will devote disproportionate resources to suppressing evidence and protecting themselves rather than accepting responsibility. The framework also incorporates the phenomenon of escalating commitment: as individuals invest more heavily in a failing course of action (such as covering up initial corruption), they become increasingly willing to commit further violations to justify their earlier decisions.

Lambsdorff’s work on the institutional economics of corruption emphasises that corrupt transactions depend on unenforceable agreements between parties who cannot seek legal recourse. His concept of the “invisible foot”—where the unreliability of corrupt counterparts creates internal tensions within corrupt networks—suggests that strategic interventions can exploit these vulnerabilities.

To put these principles into practice, we devised a methodology that deliberately provokes and aggressively litigates, triggering the natural tendencies that lead dishonest government officials to commit more overt misconduct. This approach is orchestrated so that the misconduct can be carefully documented and recognised as a detrimental reaction driven by fear of exposure.

Once confronted with evidence of their misconduct, corrupt officials must increasingly manipulate official records and enlist accomplices to suppress the truth and construct a consistent counter‑narrative. This process typically involves progressively more exaggerated depictions of their target, serving as retroactive justifications for harsh measures and generating what we call “folklore”—narratives in which exaggeration grows as the gap between reality and the official account widens. Ultimately, when the underlying documents are examined, the discrepancy between the recorded facts and the official claims becomes impossible to ignore or rationalise, and the documentary record becomes definitively incriminating.

Mechanisms of Regulatory Capture and Profiteering

Senior VLSB officials appear to be involved in a financially motivated corruption scheme. They appoint loyalists as managers of suspended law practices, who then charge hundreds of thousands of dollars to government fidelity funds. Ostensibly, these managers are appointed to protect client interests when a practitioner’s licence is suspended. However, the unrefuted evidence demonstrates systematic misuse of this process for patronage and personal gain.

By paying these managers directly from the Public Purpose Fund, rather than seeking reimbursement from the targeted firms, the VLSB avoids judicial scrutiny through cost assessment proceedings that could expose the illegality of these arrangements.

This pattern is characteristic of regulatory capture, in which a regulator promotes special interests rather than the public interest, using statutory authority for improper private gain. Academic literature on regulatory capture typically identifies three mechanisms: the “revolving door” (career incentives that encourage favouritism towards regulated entities), information capture (regulators’ reliance on industry‑supplied data), and cultural capture (shared worldviews between regulators and those they regulate). The evidence here points to an additional variant: the creation of a parasitic patronage network that directly profits from regulatory actions, thereby creating perverse incentives to maximise them regardless of their merit.

The Prostitution Allegations and Institutional Knowledge

Over time, lawyers who felt oppressed by the VLSB and became aware of our aggressive litigation and public campaigns against the organisation began sharing evidence of alleged misconduct by senior VLSB officials. They relied on us to use this information to hold those officials accountable.[1]

Among the most explosive allegations to surface is a claim that one of the most senior VLSB officials, Ms Joanne Jenkins, engaged in unregistered sex work, allegedly servicing only members of the legal profession immediately before her employment at the VLSB, after which she rapidly rose through the ranks to become one of the most prominent figures in its external intervention program.

We received video material said to document Ms Jenkins’ unregistered sex work from a whistleblowing lawyer, Mr Thomas Flitner, who also asserted that the Commissioner, Ms Fiona McLeay, had been informed of these issues years earlier. According to Mr Flitner, Ms Jenkins had solicited him as a client for her unregistered sex work and later played a key role in external intervention steps that resulted in the systematic destruction of the firm he had built over his career. Instead of investigating whether this apparent conflict of interest compromised the integrity of the adverse actions taken against Mr Flitner, he reports that the Commissioner threatened him with further regulatory measures and police complaints if he continued to raise the matter.

When we informed the VLSB of our intention to submit this material to the courts and to publish it widely—to highlight the incompatibility of certain senior officials’ alleged conduct with the character requirements for their roles under the relevant statutory instruments and common-law principles governing the profession—the VLSB sought Federal Court injunctions to prevent publication. It claimed that disclosure would cause organisational collapse and disrupt regulatory functions.

The Court initially issued interim partial suppression orders preventing the identification of specific individuals until the VLSB’s application could be determined. However, it did not prohibit broad criticism of the organisation or generalised allegations against its officials.[2]

At the final hearing, Justice Lee overturned the partial interim suppression orders, repeatedly describing the VLSB’s application as “misconceived” and characterising it as an improper attempt by the regulator to silence constitutionally protected political communication.[3]

Paradoxically, by seeking judicial intervention, the VLSB was forced to confirm key aspects of the material and the seriousness of the threat it perceived—precisely the dynamic predicted by the Folklore Effect framework. As we pointed out in court, “you don’t say all of those things unless they are true,” and the judicial decision now publicly records the failure of the VLSB’s attempt to restrain publication.

The VLSB, while explicitly refusing to deny the above allegations (despite repeated invitations from us and the judge), again sought to have them suppressed in a proceeding before Justice Finanzio in the Supreme Court of Victoria, but was unsuccessful.[4]

The Chilling Effect on Accountability: Why Lawyers Won’t Sue Their Regulator

This case highlights a fundamental structural barrier to accountability: lawyers subjected to regulatory abuse often adopt a defensive posture rather than mounting aggressive legal counterattacks, fearing career‑ending repercussions. Virtually no one sues the VLSB for misfeasance in public office or pursues other robust remedies, despite what appear to be clear grounds to do so.

Misfeasance in public office—a tort available when public officials knowingly or recklessly misuse their authority with the intention of causing harm, or with reckless disregard as to whether harm will result—offers a theoretical remedy for such abuse. To succeed, a claimant must prove:

- invalid or unauthorised acts;

- committed maliciously or with reckless indifference;

- by a public officer;

- in the course of their official duties;

- that caused loss or damage.

Establishing the requisite mental state is particularly challenging. Plaintiffs must prove either “targeted malice” or “reckless indifference” regarding both the limits of authority and the likelihood of harm. The evidentiary burden is substantial, especially given the need to demonstrate the official’s mindset to the civil standard while respecting the Briginshaw principle, which requires strong evidence for serious allegations.

Pursuing such claims also risks provoking precisely the forms of retaliation that the Folklore Effect predicts. This creates a vicious cycle: the regulator’s most serious abuses tend to be inflicted on those least able to resist, and attempts at resistance can trigger further abuse.

The case of Peter Mericka illustrates this pattern. After publicly accusing the VLSB and the broader Victorian legal system of corruption, Mericka faced disciplinary action. His membership of the Law Institute of Victoria (LIV) was used against him when his professional body accepted a delegation from the same regulator he had accused, ultimately leading to his removal from the roll. The Victorian Supreme Court dismissed his corruption claims as “scandalous and without foundation” without conducting a detailed inquiry into their merits. Mericka continues to maintain publicly that the evidence supports his allegations.

The Complicity of Professional Associations and Judicial Structures

The VLSB’s conduct demonstrates how professional associations and courts can, in practice, shield an embattled regulator. When Mericka approached the Law Institute of Victoria for help with corruption complaints against the VLSB, the LIV initially assisted him. It then accepted a delegation from the VLSB to investigate Mericka himself—effectively switching sides and supporting the body he had accused.

This manoeuvre exemplifies what we describe as the regulator’s ability to “recruit additional help” by making representations that distort the target’s character. Professional associations, judges, and other officials may cooperate with a regulator not because they are themselves corrupt, but because they accept the regulator’s negative characterisations of the target as truthful. The regulator’s institutional authority lends credibility to these characterisations, particularly when they are embedded in official records, correspondence, and court filings.

The danger, as the Folklore Effect predicts, is that as these characterisations become more extreme to justify increasingly severe measures, the eventual emergence of documentary evidence creates an unbridgeable credibility gap. Those who cooperated based on the regulator’s representations risk becoming implicated in the broader deception, thereby generating institutional incentives to prevent exposure that extend well beyond the original misconduct.

The Suppression of Government Corruption Information: Constitutional Implications

The VLSB’s attempt to obtain injunctions to prevent publication of material said to evidence corruption raises fundamental questions about the permissible limits of prior restraint on political communication concerning government misconduct. Australian courts have long recognised an implied freedom of political communication in the Constitution as essential to the system of representative government. The publication of evidence regarding corruption in public institutions falls squarely within the core of this protected sphere of communication.

We have consistently argued that “you cannot suppress evidence of government corruption from being published online.” The VLSB’s claimed need to conceal information in order to prevent organisational collapse and preserve regulatory capacity actually strengthens the public‑interest case for transparency. If revealing truthful information about officials’ conduct would cause an institution to collapse, this strongly suggests that the institution’s ongoing viability depends on concealing information the public is entitled to know—precisely the situation in which disclosure is most essential.

Implications for Rule of Law and Democratic Accountability

Regulatory abuse of the kind outlined here depends on several systemic vulnerabilities in oversight structures:

Power Asymmetries and Predatory Regulation

When regulators possess broad pre‑emptive powers but operate without robust oversight, they can target vulnerable groups while avoiding those with the resources and influence to resist. This dynamic turns the regulatory purpose into a mechanism of oppression.

The Accountability Paradox

Those most severely victimised by regulatory abuse are usually least able to seek accountability, while those best positioned to resist are least likely to be targeted. This selection effect allows systematic abuse to persist, precisely because it is focused on the vulnerable.

Institutional Corruption’s Self‑Protecting Nature

Once corruption becomes entrenched, institutions designed to provide accountability—such as professional associations, courts, and investigative bodies—may themselves be captured, weakened, or misled. The result is a self‑protecting system that resists reform and shields its own misconduct.

The Limits of Whistleblower Protection

Despite statutory protections, whistleblowers alleging institutional corruption often face retaliation executed through ostensibly legitimate regulatory and legal processes. Where the regulator itself is the alleged wrongdoer, existing protective mechanisms may prove ineffective.

Credibility Erosion Through Folklore‑Effect Dynamics

As a regulator exploits its institutional platform to vilify its targets and leverages its influence over other agencies and media outlets to endorse and amplify false or exaggerated allegations, targeted individuals lose credibility in the eyes of both the public and the very institutions whose support they need to vindicate their rights and expose the truth.

Documentary Evidence as the Ultimate Arbiter

The Folklore Effect framework maintains that meticulous documentation of interactions with corrupt officials, combined with strategic provocation that escalates misconduct, can eventually produce a body of evidence capable of breaching institutional defences. Our three‑year documented trials represent an attempt to apply this strategy in practice.

Conclusion

The matters outlined here, supported where possible by public records and judicial findings, demonstrate how regulatory systems intended to protect the community can be manipulated into instruments of institutional corruption. The Folklore Effect framework offers a useful lens for understanding how such misconduct evolves and how careful documentation can be used strategically to establish accountability.

The patterns identified in this case—targeting vulnerable practitioners, acting on weak or non‑existent evidence, resisting scrutiny, and turning professional disciplinary processes into weapons—expose systemic weaknesses that extend well beyond any single incident or individual.

The rule of law depends on checks and balances that remain effective even when those in power act in bad faith. When regulatory bodies created to serve the public instead exploit the vulnerable; when professional associations abandon their members to appease regulators; and when courts accept highly prejudicial narratives without insisting on strong evidentiary foundations, the entire system of legal accountability is put at risk. Restoring trust requires more than addressing isolated instances of misconduct: it demands a fundamental rebalancing of power, designed to ensure that no institution can operate without meaningful oversight.

The true test of a legal system’s integrity is not how it resolves clear‑cut disputes between right and wrong, but whether it can police itself when those responsible for enforcement are credibly accused of being the violators. On this measure, the Victorian experience suggests that substantial work still remains to be done.

The Path Forward: Structural Reforms and External Accountability

Addressing regulatory capture and abuse requires structural interventions, including at least the following:

Independent Oversight with Real Investigative Power

Corruption allegations against regulators must be examined by genuinely independent bodies equipped with adequate resources and authority. While IBAC theoretically performs this role, our evidence suggests it is largely ineffective when corruption is systemic rather than confined to isolated acts.

Restriction of Pre‑emptive Suspension Without Notice

The Tricarico decision confirms that immediate suspension without prior notice and an opportunity to be heard breaches procedural fairness unless there is compelling evidence of imminent danger. Legislative reform should strictly limit such powers and require clear, cogent evidence before any pre‑emptive action is taken.

Mandatory Recording and Disclosure of Regulatory Communications

A statutory requirement for comprehensive recording of all material regulatory interactions—combined with automatic provision of relevant records to affected practitioners—would create the documentary trail necessary to identify and prove abuse, while also deterring misconduct.

Asymmetric Cost Allocation

Where regulatory actions are found to be unlawful, unreasonable, or lacking a proper evidentiary foundation, automatic punitive costs orders against the regulator would reinforce financial accountability and discourage frivolous or retaliatory interventions.

Protection for Offensive Legal Action

Explicit statutory protection against retaliation for initiating legal action against regulators—including misfeasance claims and applications for judicial review—would mitigate the chilling effect that currently deters many from seeking redress.

Public Transparency of Disciplinary Proceedings

Subject to appropriate safeguards in genuinely sensitive cases, the default position should be that disciplinary proceedings are public and that the underlying evidence is published in full, particularly when severe sanctions are being considered. Sunlight remains the best disinfectant.

Endnotes

[1] The affidavit of Mr Thomas Flitner listing the allegations is available here: https://workdrive.zohopublic.com.au/file/5oto6e250c1cfdae744a0adafb2c3743f91d8

[2] Victorian Legal Services Board v Kuksal [2025] FCA 558

[3] Victorian Legal Services Board v Kuksal (Interlocutory Matters) [2025] FCA 801 [26]-[29]

[4] Kuksal v State of Victoria & Ors [2025] VSC 663