I. Background

The allegations concerning the Victorian Legal Services Board [VLSB] discussed in this article are based on Thomas Flitner’s affidavit[i] filed in our ongoing proceedings against the VLSB in the Supreme Court of Victoria, as well as his interview with us. The interview clips are available in the following playlist:

https://www.youtube.com/playlist?list=PLZJqwhjmeUd6DNDMiX2iPIKgSd-0jgS8P

This article is intended to be read as a supplement to the video clips above, which provide a more comprehensive account and additional context for the factual matters discussed here.

All of the matters raised in this article are presently being advanced, supported by extensive documentary evidence, in multiple ongoing proceedings that we have commenced against the VLSB, including the proceeding referred to in the related article.[ii] Despite being questioned about these matters by Justice Finanzio, the VLSB has failed to address the allegations substantively and has simply maintained that it considers them to be irrelevant.

Many other lawyers have independently raised similar concerns with us about these issues.

A. The Destruction of a Small‑Firm Practice

For more than two decades, Thomas Flitner operated a suburban law firm in Greensborough, Victoria, building a practice that primarily served middle‑income clients in Melbourne’s northern suburbs. His trajectory from established practitioner to dispossessed professional began not with serious misconduct, but with the exercise of his legal rights: challenging a disciplinary sanction through Victoria’s courts.

Years before the events at issue, the Victorian Legal Services Board (VLSB) commenced disciplinary proceedings against Flitner. He contested the matter through all available appellate channels and ultimately prevailed before the Victorian Court of Appeal, which held that the sanction imposed by the Victorian Civil and Administrative Tribunal (VCAT) was “manifestly excessive.” This success was, however, pyrrhic. The Court of Appeal also ordered the Board to pay Flitner’s costs—approximately $80,000—a rare outcome in regulatory proceedings and a public indication that the Board had overreached.

According to Flitner, this outcome did not prompt institutional reflection but instead marked him out for heightened scrutiny. He claims that, following his Court of Appeal victory, the VLSB subjected him to what he describes as “relentless regulatory pressure.” After further contentious dealings between Flitner and individuals connected with the VLSB, this pressure culminated in October 2023, when two men—Gordon Cooper and Nick Curran—arrived at his office while he was at home unwell and announced that they were “taking over” the practice he had spent more than twenty years building.

Flitner later discovered that Cooper had not, in fact, been employed or properly engaged by the VLSB, but was apparently present at the personal behest of Howard Bowles, a senior manager at the VLSB who, according to Flitner, played a critical role in destroying his practice.

The intervention in Flitner’s practice occurred without prior notice or service of any documents. He was given no opportunity to seek clarification from the VLSB or to apply to the Supreme Court for an injunction to halt the seizure. Within a few months, his practice was transferred to another firm, De Maria Associates, for no consideration. Flitner was neither bankrupt nor struck off the roll of practitioners; as he succinctly observed, “They just took it. That’s not regulation—that’s theft.”

B. Flitner’s & Others’ Allegations Against the VLSB

According to Flitner, the VLSB has, for more than a decade, systematically abused its statutory powers to destroy his Greensborough practice, punish him for challenging the regulator and lodging complaints against its senior staff, and intimidate both him and his lawyers, as part of what he claims is a broader pattern of institutionalised regulatory “lawfare” against detractors.

Framing and Scope of Flitner’s Allegations

Flitner contends (as do many other Victorian lawyers) that senior VLSB officials—including Howard Bowles, Fiona McLeay and others he terms “Corrupt VLSB Officials”[iii]—have engaged in a long‑running “campaign of persecution” against him, without lawful justification, causing severe financial, psychological and reputational harm.

He situates his experience within what he alleges is a broader pattern of systemic abuse of authority by the VLSB and the Legal Services Commissioner, drawing on the 2009 Brouwer Ombudsman report and on similar experiences reported by the “VLSB Action Group,” comprising affected practitioners and members of the public.

The affidavit is expressly tendered in support of contempt and related proceedings against VLSB officials. Through his case, Flitner seeks to demonstrate what he characterises as a deliberate and organised misuse of regulatory powers and of the Public Purpose Fund (PPF), deployed as instruments of oppression and unjust enrichment.

Details of Flitner’s Allegations

According to Flitner, the Corrupt VLSB Officials improperly weaponise the powers entrusted to the VLSB under the Legal Profession Uniform Law Application Act 2014 (Vic) and the Legal Profession Uniform Law (Vic) [Uniform Law] to:

- Oppress and vilify individuals [Targeted Individuals], instituting or expressing an intention to institute administrative or judicial proceedings to raise complaints against the Corrupt VLSB Officials [VLSB’s Dissident Persecution], by:

- Disrupting their law practices’ operations and their commercial relationships through the abuse of the VLSB’s regulatory functions. This is achieved, in part, by issuing unwarranted and oppressive (and in some cases, unauthorised) Management System Directions [MSD]s;

- Unlawfully confiscating their private property, contravening their right to privacy and legal privilege and privilege against self-incrimination, as well as destroying the goodwill and commercial worth of their businesses by exploiting the VLSB’s external intervention powers;

- Inciting and/or coercing the Targeted Individuals’ employees and agents to breach their duty of confidence and loyalty to them and cooperate in the institution of unconscionable prejudicial actions against them through fraud;

- Improperly interfering in their[iv] clients and their court proceedings through seemingly arbitrary but, in fact, opportunistically timed determinations concerning the suspension/non-renewal of practising certificates, self-evidently aimed at causing maximum prejudice to the Targeted Individuals and their clients’ legal rights and sabotaging their legal representation in trials, including those against the VLSB and State agencies improperly coordinating with the organisation;

- Maliciously prosecuting the Targeted Individuals for offences under the Uniform Law based on spurious allegations and, in some cases, untenable allegations and fabricated evidence;

- Colluding with corrupt prosecutors at Victoria Police to fraudulently obtain convictions against the Targeted Individuals, including through the sabotage of their legal representation just before trials and the facilitating unauthorised disclosure of information contained in files seized from their practices to Victoria Police, in contravention of their right to privacy, client legal privilege and privilege against self-incrimination; and

- Taking adverse actions against the lawyers who represent the Targeted Individuals to impede them in obtaining legal representation or to prevent their lawyers from acting in fidelity to their statutory and common law obligations to the Targeted Individuals.

- Abuse the VLSB’s access to and influence over administrative and judicial officers at various State and Federal Courts (and administrative tribunals) to deny the Targeted Individuals their rights to due process, equality under the law, and fair and public hearings before competent, independent and impartial tribunals by:

- Ensuring that the VLSB’s applications against the Targeted Individuals get preferential listing and those made by the Targeted Individuals are either improperly rejected or persistently delayed;

- Influencing judicial and administrative decision-makers through clandestine and ex parte correspondence to make unauthorised decisions against the Targeted Individuals;

- Unlawfully colluding with and exchanging unauthorised confidential documents concerning the Targeted Individuals with other government agencies in contravention of their right to privacy, client legal privilege and privilege against self-incrimination;

- Vilifying the Targeted Individuals by exploiting the VLSB’s connections with reporters and media entities, including and causing the publication of spurious and inflammatory allegations about the Targeted Individuals just before trials, to prejudice judges and juries, as well as turn the public opinion against them;

- Improperly introducing spurious and/or unfairly prejudicial allegations against the Targeted Individuals in proceedings;

- Abusing the court process to frustrate or thwart the determination of the claims made by the Targeted Individuals against the Corrupt VLSB Officials by:

- Misleading the court and abusing technicalities;

- Employing unethical manoeuvres such as refusing to concede incontestable issues to incur additional delay and costs for the Targeted Individuals, frequently changing their counsel to seek adjournments or concessions for failing to adequately assist the Court in respect of factual and legal elements of the matters; and

- Obtaining exorbitant costs orders on oppressive terms of enforcement that circumvent or effectively frustrate the enforcement of the Targeted Individuals’ statutory rights regarding the costs assessment and taxation of legal bills of costs; and

- Obtaining determinations and orders by incontrovertible fraud, including through the suppression of documents critically relevant to the disputes between the parties when they are prejudicial to the VLSB’s case.

- Knowingly cause the Victorian Legal Services Commissioner to employ individuals [Manipulable Employees] whose inclusion in the legal profession brings it into disrepute, in part, to:

- Exercise improper control over them and compel them to take unjustifiable adverse actions against the Targeted Individuals; and

- Exploit the compromising information they may possess about individuals in positions of influence in other government agencies or corporations.

One of the Manipulable Employees, Joanne Jenkins, who has allegedly exploited the connections she developed while working as an unregistered sex worker[v] to secure employment by the Victorian Legal Services Commissioner and rapidly ascend within the organisation to her current position as the person responsible for overseeing the VLSB’s external intervention actions in respect of law practices.

While in the role, Jenkins oversaw the VLSB’s seizure and destruction of Flitner’s law practice between 11 October 2023 and 10 October 2024, despite having previously solicited him as a client while working as an unregistered sex worker, over several months beginning in June 2019 [Flitner Solicitation], first through SugarDaddy.com and later through phone calls, electronic communication and in person.

During the Flitner Solicitation, on 4 June 2019, Jenkins sent Flitner nine graphic videos [Jenkins Graphic Videos], uninvited, depicting her engaging in various sexual acts with multiple individuals, in private and public locations, including in the restrooms of commercial office buildings.

At least by early April 2024, both McLeay and Bowles were aware[vi] of Jenkins’ past unregistered sex work and that she had sent the Jenkins Graphic Videos to Flitner, uninvited. Nonetheless, neither McLeay nor Bowles felt that Jenkins’ involvement in Flitner’s case was improper.

When Glenn Thexton raised concerns to McLeay on Flitner’s behalf in early April 2024, she dismissed them outright and refused to investigate their complaints.

McLeay also threatened Thexton and Flitner with criminal charges for harassment and unlawful distribution of sensitive and intimate information if they persisted in drawing public attention to the matter, through her solicitor, Alex Wolff.[vii]

Based on representations made by Bowles to Thexton via phone calls and email correspondence in or around April 2024, Thexton and Flitner formed the view [Bowles Blackmail Inference] that Bowles may have been improperly leveraging his awareness of Jenkins’ past work as an unregistered sex worker to pressure her into making improper decisions in her role as the VLSB manager of external interventions, contrary to her statutory obligations.

Thexton and Flitner were further fortified in respect of the Bowles Blackmail Inference, when Wolff, on behalf of McLeay, sought to assure [Bowles Conflict Admission] them that both Jenkins and Bowles “have no ongoing role in any legal regulatory matters relating to you and Flitner and so regardless there is no potential for conflict moving forward” on 10 April 2024. It is worth noting that Thexton had previously raised concerns only regarding Jenkins’s conflict of interest in Flitner’s matters.

Following the Bowles Conflict Admission, Thexton asked McLeay to investigate Flitner’s and his concerns regarding the Bowles Blackmail Inference, by responding to Wolff’s correspondence the same day (10 April 2024).

In response, on 12 April 2024, McLeay conveyed through Wolff that “there is no conflict of interest” and “there will be no ‘further investigation.’”

- Unjustly enrich[viii] [External Intervention Scam] their confidants [VLSB Cronies][ix] by appointing them as external intervenors[x] and permitting them to charge exorbitant fees [Exorbitant PPF Bribes], which are approved without any oversight mechanism and immediately disbursed from the Public Purpose Fund [PPF].[xi]

As the Targeted Individuals or their practices do not pay the Exorbitant PPF Bribes, the VLSB Cronies refuse to provide them with detailed bills of costs or justification for the inexplicable amounts charged, despite the invoices being issued in the names of the Targeted Individuals or their practices.[xii]

Sometime after the VLSB Cronies have been paid the Exorbitant PPF Bribes, without any oversight mechanism, the Corrupt VLSB Officials then pursue the Targeted Individuals to seek reimbursement of the Exorbitant PPF Bribes, thereby ensuring that the Targeted Individuals are saddled with the liability of the bills charged by the VLSB Cronies, even as they effectively negate their statutory right to seek review and taxation of those bill under the Uniform Law.[xiii]

Critically, the unjust enrichment of the VLSB Cronies to contravene the statutory objectives and jurisdictional facts underpinning the VLSB’s power to authorise external intervention as set out in sections 323 and 326 of the Uniform Law is the essential feature of the External Intervention Scam.

The VLSB Cronies are completely uninterested in serving the interests of the clients, associates, and owners of the practices to which they are appointed. The sole purpose motivating their conduct is the destruction of the practices and the infliction of maximum harm on the Targeted Individuals.

The purpose behind the Corrupt VLSB Officials securing the Exorbitant PPF Bribes for the VLSB Cronies is to ensure their cooperation in taking detrimental actions against the Targeted Individuals by abusing their control over their practices and access to confidential and privileged information concerning them to assist the Corrupt VLSB Officials in:

- Unlawfully seizing their assets;[xiv]

- Destroying the business worth of their law practices and rendering them insolvent;[xv]

- Weaponising the information gained from confidential and privileged documents by:

- Commencing proceedings and disciplinary actions against the Targeted Individuals and incitement of other law enforcement agencies to commence criminal prosecutions against them, in contravention of the Targeted Individuals’ privilege against self-incrimination and client legal privilege;

- Unlawfully disclosing the information to entities in conflict with the Targeted Individuals so that they may weaponise it in court proceedings against the Targeted Individuals or to unfairly prejudice them;

- Clandestinely releasing the information about the Targeted Individuals, including personal and sensitive information, to the Corrupt VLSB Officials’ media contacts to vilify them; and

- The direct surreptitious distribution of the information to courts and tribunals before which the Targeted Individuals have extant proceedings (without the knowledge of the Targeted Individuals) to prejudice decision-makers and secretly seek adverse determinations against them, to use as the basis of adverse actions against them. This is done under the guise of the performance of the VLSB’s investigative functions.

Moreover, the Corrupt VLSB Officials often exploit the services of the VLSB Cronies without proper instruments of delegation, creating the ostensible impression that they are legitimately involved in external intervention roles or employed by the Victorian Legal Services Commissioner to cause malicious harm to the Targeted Individuals, which may be problematic to pursue following their formal appointments.

Such arrangements are also secured through the payment of the Exorbitant PPF Bribes.

- The Corrupt VLSB Officials frequently abuse the Court’s bankruptcy jurisdiction in oppressive ways to vilify the Targeted Individuals, depriving them of their legal rights and ruining them financially as a means to:

- Causing malicious harm to the Targeted Individuals;

- Preventing them from accessing accountability measures against the Corrupt VLSB Officials; and

- Discouraging others from seeking to hold the Corrupt VLSB Officials.

II. The Mechanics of Regulatory Seizure: External Intervention Powers

A. The Legal Framework

Victoria’s Legal Profession Uniform Law confers extensive powers on the VLSB to intervene in the operation of law practices by appointing external managers, supervisors or receivers. These powers exist on a statutory continuum:

- Supervisors manage a practice’s trust accounts only and are typically appointed when inadequate handling of client funds is suspected.

- Managers assume control of the entire practice, with authority to supervise operations, analyse business systems, implement compliance measures, wind up affairs and terminate operations if deemed “appropriate”.

- Receivers, appointed by the Supreme Court on a VLSB application, attempt to recover trust money or property in cases of suspected misappropriation.

The ostensible purpose of these interventions is consumer protection: safeguarding client funds and legal matters when a practice “fails to, or is unable to, protect the interests of its clients”. Circumstances said to warrant intervention include alleged improper conduct, insolvency, ill health or the death of the principal. The regulatory statement emphasises that interventions range from supervisory oversight to complete takeover, with the stated objective of protecting clients, the practice itself, employees and the public.

The Legal Profession Uniform Law External Intervention Procedures Manual—used across multiple jurisdictions—specifies that managers may be appointed subject to conditions, reporting requirements and specified terms. Critically, it provides that “the law practice may appeal against the appointment”, acknowledging a fundamental procedural safeguard. The manual also requires notification to affected parties and prescribes procedures for handling regulated property.

B. The Reality: Intervention as Destruction

The Flitner case reveals how these powers may operate in practice when accountability mechanisms fail. According to Stephen Walters, the solicitor who represented Flitner, the VLSB and its appointed manager, Nicholas Curran, deliberately destroyed the law firm rather than preserving it. Walters’ letter to the VLSB catalogued what he described as systematic demolition:[xvi]

Immediate operational cessation: The firm was shut down without notice despite having ongoing client matters.

Summary staff termination: All employees were abruptly dismissed, leaving clients without representation. At least one employee was reportedly so traumatised she had to leave her home.

Communications blockade: Client emails were blocked, including access to Flitner’s personal account, severing lawyer–client relationships and preventing an orderly transition.

Asset seizure: Office computers were allegedly taken without legal authority, preventing access to client files and business records.

Client abandonment: It is alleged that no meaningful effort was made to manage the practice. Clients were reportedly told to “go elsewhere” for legal assistance.

File withholding: Important client files were withheld, potentially causing serious harm to ongoing legal matters.

Alternative rejection: The Board allegedly ignored repeated offers from Walters for an orderly takeover of Flitner’s firm that would have preserved employment, protected client interests, and maintained the practice as a going concern.

This pattern, which many other practitioners have also complained of, contradicts the stated regulatory objective of protecting clients and suggests alternative motivations. When a regulatory intervention causes greater harm to clients than the conduct it purports to address, the intervention itself becomes a form of malfeasance.

C. The Manager: Nick Curran and the External Intervention Panel

Nick Curran, the manager appointed to Flitner’s practice, is a partner in the commercial litigation and insolvency practice at Thomson Geer, a major Australian law firm. Significantly, Curran serves on the VLSB’s External Intervention Panel and has been repeatedly appointed to manage law practices that have been subject to regulatory seizure.

Recent VLSB public statements reveal the frequency of such appointments. In January 2025, Curran was appointed as manager of Zora Law Pty Ltd; in April 2025, he and colleague Bronwyn Lincoln were appointed as managers of Dojo Partners Pty Ltd and Visatec Legal Pty Ltd. In fact, Curran and a handful of others, such as Howard Rapke of Holding Redlich, have received multiple, often simultaneous, appointments from the VLSB each year over the last few years. These recurring appointments raise essential questions about the structure of Victoria’s external intervention system and the incentive architecture governing private contractors who profit from regulatory enforcement actions.

The External Intervention Panel operates through an expression‑of‑interest process, in which the VLSB identifies “suitable candidates” to provide supervisory, management, and receivership services. Panel membership does not constitute a contract for services; instead, it creates eligibility for appointment “as the need arises.” This structure creates a pool of private practitioners who depend on the VLSB for lucrative appointment opportunities, potentially compromising their independence and creating perverse incentives to support aggressive enforcement.

III. Procedural Fairness Violations: The Denial of Natural Justice

The circumstances of Flitner’s intervention, as described, constitute egregious alleged breaches of administrative law principles that form the bedrock of legitimate government action in Westminster legal systems. Procedural fairness—a precondition for natural justice—requires that administrative decision‑makers afford affected persons notice and an opportunity to be heard before making decisions that adversely affect their rights, interests, or legitimate expectations.

A. The Common Law Duty

Australian courts have consistently held that “in the absence of a clear, contrary legislative intention, administrative decision‑makers must accord procedural fairness to those affected by their decisions.” This duty arises at common law and can only be excluded by express statutory language or necessary implication from legislative structure. The High Court has emphasised that denial of procedural fairness by a Commonwealth officer, where the duty has not been validly limited or extinguished by statute, results in a decision made in excess of jurisdiction—a fundamental jurisdictional error attracting constitutional remedies.

The content of procedural fairness varies with context, but generally encompasses two core requirements: the fair hearing rule and the rule against bias. The fair hearing rule, rooted in the maxim “audi alteram partem” (hear the other side), requires decision‑makers to provide affected persons with notice of adverse material, an opportunity to respond, and adequate time to prepare. The rule against bias demands objective impartiality: decision‑makers must be free from actual bias, apprehended bias, and prejudgment.

As Mason J articulated in Kioa v West, “the fundamental rule is that a statutory authority having power to affect the rights of a person is bound to hear him before exercising the power.” This principle reflects deeper constitutional values: the separation of powers, restraint on executive action, and protection of individual liberty against arbitrary state power.

B. Application to External Interventions

External intervention in a law practice unquestionably affects rights and interests of considerable significance. A lawyer’s practising certificate represents not merely a commercial licence but professional identity, livelihood, reputation, and the product of years of education and training. Seizure of a law practice affects property rights, contractual relationships, employee livelihoods, and client interests. Courts have consistently held that administrative actions with such profound consequences trigger the highest level of procedural protection.

The Legal Profession Uniform Law does not expressly exclude procedural fairness for external interventions. Indeed, the External Intervention Procedures Manual acknowledges appeal rights and contemplates notice procedures. Regulation 97 of the Legal Profession Uniform General Rules 2015 provides that instruments appointing supervisors must “include a statement that the law practice may appeal against the appointment,” explicitly recognising procedural safeguards.

Yet, on Flitner’s account, he received no notice whatsoever. He was not served with documents explaining the grounds for intervention. He was afforded no opportunity to respond to allegations or present mitigating circumstances. He could not seek clarification from the Board or apply to the Supreme Court for interim relief. The intervention occurred while he was unwell at home, maximising his vulnerability and inability to respond. This, if accurate, would constitute a textbook denial of natural justice.

C. The Emergency Exception and Its Limits

Administrative law recognises that emergency circumstances may justify abbreviated procedures or even post‑hoc hearings where immediate action is necessary to prevent imminent harm. Emergency powers legislation typically provides for temporary derogation from constitutional norms when ordinary processes cannot cope with crises. However, several strict conditions govern the legitimate use of emergency procedures:

Genuine emergency: There must be an actual crisis requiring immediate response; convenience does not suffice.

Proportionality: Emergency measures must be tailored to the specific threat and no more intrusive than necessary.

Temporal limitation: Emergency powers must be time‑limited and subject to regular review.

Judicial oversight: Courts retain review jurisdiction even during emergencies, applying heightened scrutiny to executive claims of necessity.

Procedural integrity: Even emergency actions must respect core due process values; abbreviated procedures do not mean no procedures.

The Flitner intervention, based on the available material, fails to meet any of these criteria. Many other practitioners complain of similar experiences with the VLSB. Remarkably, the VLSB takes such actions when no evidence suggests an imminent risk to client funds or an acute operational crisis requiring immediate seizure. Flitner was not accused of absconding with trust money, actively destroying files, or engaging in ongoing criminal conduct. He had successfully operated the practice for over twenty years. The only apparent “emergency” was the VLSB’s desire to act without judicial scrutiny.

Moreover, the intervention was not temporary but permanent: the practice was transferred to another firm and ceased to exist as a legal entity. This was not crisis management but capital punishment—the corporate death penalty imposed without trial. As scholars examining emergency powers have warned, the danger lies in emergency measures becoming normalised, deployed “for the sake of convenience” rather than desperate necessity. The Flitner case exemplifies this pathology: extraordinary powers originally justified by exceptional circumstances repurposed for routine regulatory enforcement.

IV. The Retaliation Thesis: Regulatory Capture and Institutional Vengeance

A. Temporal Correlation and Circumstantial Evidence

The chronology of Flitner’s ordeal invites uncomfortable questions about regulatory motivation. His problems with the VLSB began with disciplinary proceedings that he successfully challenged on appeal. The Court of Appeal’s finding that VCAT’s sanction was “manifestly excessive” represents a judicial rebuke of both the tribunal and the prosecuting regulator. The additional costs award of $80,000 compounded the institutional embarrassment by requiring the Board to compensate the practitioner it had sought to discipline financially.

Following this defeat, Flitner describes experiencing “relentless regulatory pressure,” characterised by heightened scrutiny and ongoing investigations. His situation only worsened once he started making serious allegations against senior VLSB officials. The October 2023 intervention—occurring years after these matters—completed the pattern: initial overreach, judicial reversal and calls for further scrutiny, intensified surveillance, and ultimate destruction through administrative means that bypass court review.

This sequence is consistent with classic retaliation: an adverse professional action (intervention/seizure) following protected activity (exercising appeal rights) in circumstances suggesting a causal connection. While temporal proximity alone does not prove retaliatory motive, the clustering of aggressive regulatory action around Flitner’s successful appeal and subsequent complaints creates a robust inference of institutional animus.

Many other practitioners share Flitner’s experience, and some of their cases are discussed in related publications.

B. Regulatory Capture and Professional Self‑Regulation

The academic literature on regulatory capture provides theoretical framing for understanding how professional self‑regulation can become corrupted. Regulatory capture occurs when an agency is “controlled or unduly influenced by” the entities it regulates, leading to regulatory decisions that serve private interests rather than the public good. The phenomenon exists on a spectrum from subtle bias to complete co‑option:

- At a first level, regulators allow regulated entities to breach applicable standards without meaningful enforcement.

- At a second level, regulators assist wrongdoers in avoiding consequences after violations occur.

- At the deepest level, capture is so complete that regulators actively assist the regulated in defeating the regulatory regime before violations happen.

Self‑regulation of the legal profession creates structural conditions highly conducive to capture. Lawyers regulate lawyers, creating inherent conflicts between professional solidarity and enforcement responsibility. As scholars have observed, professional associations function simultaneously as trade unions and disciplinary prosecutors—a dual role that generates “ambivalence about sanctioning colleagues” and reluctance to “tattle on one’s friends.” Small jurisdictions face particular risks when regulators must “discipline friends or even family.”

Research consistently finds that legal profession self‑regulation has experienced “deep and profound” failures. Disciplinary sanctions do not deter misconduct effectively. Lawyers do not fear bar authorities with the trepidation professionals in other fields display toward their regulators. Standardisation is lacking, giving excessive discretion to decision‑makers who may be reluctant to penalise peers. The system defaults to individual scapegoating rather than structural reform, preserving the profession’s reputation by sacrificing isolated members when public scandals demand visible action.

This literature suggests that the VLSB’s treatment of Flitner may reflect not capture by practitioners seeking weak enforcement, but a related pathology: regulatory defensiveness. When a practitioner successfully challenges Board action through judicial review, the Board faces institutional embarrassment and potential accountability. If the Board then retaliates through subsequent enforcement actions, it acts to protect its own institutional interests rather than the public good—a form of regulatory self‑dealing that betrays the fundamental premise of professional regulation.

C. The Stephen Walters and Glenn Mohammed Postscript

According to both Flitner and Stephen Walters, the VLSB has deliberately targeted and punished Flitner’s legal representatives and weaponised a baseless police prosecution in order to isolate him from effective representation and neutralise those who challenged its conduct.

Flitner’s long‑time solicitor, Stephen Walters, was subjected to what they describe as “malicious” regulatory action by the VLSB after he successfully and vigorously defended Flitner, including by criticising Victoria Police and the Board. Walters later told us he regarded these actions as retaliatory measures taken against him for his work on behalf of Flitner.

Flitner similarly alleges that his barrister, Glenn Mohammed, is now under VLSB investigation based on a “facetious” complaint apparently brought by police prosecutor Bianca Moleta, solely because he accused her of prosecutorial misconduct and successfully obtained the exclusion of prejudicial evidence. That exclusion led to the collapse of the criminal case against Flitner and a substantial costs order against Victoria Police.

Moleta had advanced the underlying criminal proceeding despite failing to disclose exculpatory material. Once that non‑disclosure was exposed, Mohammed applied under the Evidence Act to exclude the resulting “unfairly prejudicial” evidence, and succeeded. Flitner notes that the magistrate refused a costs application by police and Moleta, expressly accepted that Mohammed was entitled to raise the disclosure issue, and observed that non‑disclosure of this kind is capable of producing miscarriages of justice by pressuring accused persons into guilty pleas. Nonetheless, the VLSB declined to investigate Moleta’s conduct while opening a disciplinary investigation into Mohammed for raising concerns about it.

Flitner situates this within a broader pattern: the Board and specific senior officials collaborate with selected police prosecutors, share privileged material seized under regulatory powers, and then turn their disciplinary machinery against any practitioner who effectively resists or exposes this conduct. He claims that the Board’s seizure of his practice and the appointment of external manager Nick Curran in October 2023 were timed to coincide with a critical moment in his criminal case—after Moleta recused herself and shortly before his Evidence Act application—so that the VLSB could retrospectively use the mere existence of the charge to revoke renewal of his practising certificate and take control of his firm and files.

More generally, he alleges that the VLSB “regularly abuses” its control of practising‑certificate renewals by retroactively refusing renewals to “Targeted Individuals” in circumstances where it lacks evidence to cancel a certificate but wishes to achieve the same practical outcome: exclusion from practice and economic destruction. He asserts that this tactic was used against him. The criminal charge had been on foot since April 2021. Yet, the Board did not act until October 2023, when it both intervened in his practice and purported to reject, with retrospective effect, his 2021 renewal on “fit and proper” grounds, without giving him a meaningful opportunity to demonstrate the fragility of the police case.

On Flitner’s account, these events demonstrate a deliberate strategy by the VLSB to:

- Punish lawyers who defend targeted practitioners effectively or who criticise police and the Board;

- Exploit unresolved or weak criminal allegations as a pretext for ex post facto licensing decisions and external interventions; and

- By doing so, they deny those practitioners, including Flitner himself, their right to independent representation and access to the courts.

Our proceedings against the VLSB in the Supreme Court present unchallenged documentary evidence of similar misconduct, including correspondence sent on behalf of Bowles to a police prosecutor inviting them to gain control of legally privileged documents prepared by lawyers acting in a client’s defence, to aid in the prosecution of the client after the VLSB seized control of the practice representing that client.[xvii]

The Independent Broad‑based Anti‑corruption Commission (IBAC) later found that the police officers in question had engaged in police misconduct, including giving false sworn statements and other serious misconduct, and referred them to the Police Commissioner for disciplinary action. The police prosecutions that the VLSB had been assisting were abandoned well before this referral, once the officers’ misconduct became apparent during the court proceedings.

V. Financial Opacity and the Public Purpose Fund

A. Structure and Scale

The Victorian Public Purpose Fund (PPF) represents one of the largest trust funds in the state’s justice portfolio, valued at $3.4 billion as of 30 June 2025 (according to the VLSB’s annual statement). The fund generates income from multiple sources: interest earned on lawyers’ trust accounts and statutory deposit accounts, investment returns on the fund corpus, fees from issuing practising certificates, and fines imposed on legal practitioners. These revenues support an array of public purposes: regulating the legal profession; funding legal aid through Victoria Legal Aid; supporting community legal centres; funding law reform initiatives; supporting judicial education; and funding grants for legal research projects.

The fund’s significance extends beyond its dollar value. By pooling interest from client trust accounts across Victoria’s entire legal profession—over 25,600 practitioners holding current certificates—the PPF transforms what would otherwise be dispersed, small‑sum earnings into centralised capital available for collective public benefit.

It is worth noting that, given Victoria’s recent financial difficulties, the Victorian Government has borrowed $300 million from the PPF to fund State‑provided legal services, underscoring the PPF’s significance for Victorians.

B. The Governance Vacuum

Despite its scale and public importance, the PPF operates with remarkably little transparency or independent oversight. The Legal Profession Act 2004 requires the Attorney‑General to approve amounts paid from the fund to cover VLSB costs. It permits the Attorney to determine minimum allocations for legal aid, VCAT, and the Victorian Law Reform Commission. However, as recent reporting notes, “that approval appears purely administrative” with no evidence of substantive review or meaningful constraint on VLSB discretion.

The VLSB determines fund allocations based on “its own internal plans and policies,” but the process is “entirely opaque.” There is no independent oversight body, no public audit of expenditure decisions, and no transparent reporting on how money is actually spent beyond aggregated financial statements. The Attorney‑General’s statutory approval function appears to operate as rubber‑stamping rather than genuine accountability.

This governance vacuum creates conditions ripe for abuse. When a regulatory agency controls a multi‑billion‑dollar fund with minimal oversight and has the power to appoint private contractors to lucrative external intervention assignments, perverse incentives proliferate. The lack of transparency means affected parties cannot scrutinise costs, challenge expenditures, or verify that interventions serve public rather than private interests.

C. External Intervention as Profit Centre

The intersection between external intervention powers and PPF expenditure creates particularly troubling dynamics. According to Flitner, the VLSB uses the Public Purpose Fund to pay external managers like Nick Curran and Howard Rapke, sometimes approving “inflated or unjustified” invoices issued by these private contractors. The process is described as operating as follows:

- VLSB appoints private law firms or individual practitioners as external managers.

- These managers issue invoices for their services at commercial rates.

- VLSB pays the invoices from the Public Purpose Fund.

- VLSB then threatens to recover costs from the dismantled law practices.

- When practices attempt to challenge charges, they are told they lack standing to object because the regulator, not the firm, is technically the “client” for purposes of the management relationship.

This arrangement risks turning external intervention into a profit centre. Private contractors have a financial incentive to recommend aggressive intervention and to bill extensively once appointed. The VLSB faces no direct budgetary constraint in approving these expenditures because the costs are externalised to the Public Purpose Fund. And the practices being dismantled cannot effectively challenge the charges because they are legally deemed not to be the clients of the managers destroying their businesses.

This structure offends basic principles of financial governance and public accountability. In public administration, the entity authorising expenditure should face budgetary constraints that incentivise cost‑consciousness. Spending should be subject to an independent audit and transparent reporting. Affected parties should have standing to challenge unreasonable charges. Given the available material, the PPF system fails to meet any of these requirements, creating a closed loop of regulatory capture in which the agency, its private contractors, and the fund exist in mutually reinforcing insularity.

VI. The Failure of Oversight Mechanisms

A. The Victorian Ombudsman: Limited Powers

The Victorian Ombudsman investigates complaints about state government departments, statutory authorities, and local government—a jurisdiction that encompasses the VLSB.

In 2009, the former Victorian Ombudsman, G. E. Brouwer, conducted an own‑motion investigation into the office of the Legal Services Commissioner following 95 complaints. Brouwer found a systemic pattern of abuse of authority within those complaints.

A concise summary of the Brouwer Report, included in the Ombudsman’s annual report to the Victorian Parliament on 3 September 2009, stated:

“Over the past year, I received 95 complaints about the Legal Services Commissioner, which replaced the former Legal Ombudsman in December 2005. There were recurring themes in the complaints which pointed to a systemic failure by the Legal Services Commissioner to adequately undertake its statutory role.

For example, complainants alleged that:

- complaints were inadequately investigated or not investigated at all

- there were significant delays – sometimes in excess of three years in finalising complaints

- documentation practices were poor and failed to provide complainants with information about the Legal Services Commissioner’s internal review process and external review mechanisms

- investigations lacked procedural fairness.

…

I also conducted an own motion investigation into the Legal Services Commissioner and its decision-making processes under section 14 of the Ombudsman Act because of the number of complaints I had received. My investigation identified a lack of understanding by staff of the Legal Services Commissioner’s statutory powers and a restricted skills-set to conduct investigations. The Legal Services Commissioner’s investigators showed limited knowledge of the basic techniques of investigative processes. Case files lacked:

- investigation plans

- thorough and professional approaches to gathering evidence

- follow-up on serious allegations

- substantiating documents such as practitioners’ files

- timely conclusions

- verification of practitioners’ responses

- reasons for decisions.”

I made 28 recommendations to the Legal Services Commissioner and am pleased to note that it has taken steps to address a number of problems identified in my own motion investigation. I intend to review the Legal Services Commissioner’s implementation of my recommendations over the next year. I also referred the report of my investigation to the Attorney-General for his information, particularly in relation to the inability of the Legal Services Commissioner to re-open cases on the basis of merits.”

Unfortunately, the full report produced by former Ombudsman G. E. Brouwer (the Brouwer Report) following his investigation is not publicly available. The current Victorian Ombudsman, Marlo Baragwanath, has successfully resisted its disclosure despite persistent efforts by numerous parties to obtain it under the Freedom of Information Act 1982 (Vic).

This secrecy persists despite the continuing volume and seriousness of allegations against the VLSB since the publication of the Brouwer Report.

The fact that the Ombudsman received 95 complaints from lawyers in a single year about the Legal Services Commissioner indicates systemic dissatisfaction with the regulator’s conduct. However, the Ombudsman’s role is fundamentally recommendatory rather than coercive.

The Ombudsman can investigate, make findings, and recommend remedial action. When investigating complaints about regulatory decisions, the Ombudsman assesses whether authorities followed proper procedures, communicated clearly, and exercised discretion reasonably. The office has successfully used informal resolution to fix specific problems: recovering unpaid amounts, correcting administrative errors, and securing apologies for poor service.

But the Ombudsman cannot overturn regulatory decisions, force agencies to change their actions, or impose sanctions for misconduct. Recommendations are just that—recommendations. An agency can simply refuse to implement them. While persistent Ombudsman criticism may generate political pressure for reform, this is a comparatively weak accountability mechanism alongside judicial review or binding administrative appeals.

Moreover, in Flitner’s case, as in the cases of many other lawyers who have contacted us, the Ombudsman refused to investigate complaints against the VLSB for the reasons set out above, instead recommending that the lawyers take their matters to court.

B. IBAC: Definitional Constraints

The IBAC serves as Victoria’s primary anti‑corruption agency, responsible for identifying and exposing corrupt conduct in the public sector. However, IBAC’s jurisdiction suffers from definitional constraints that limit its effectiveness for cases like Flitner’s. The IBAC Act 2011 defines “corrupt conduct” narrowly, requiring that conduct constitute a “relevant offence” before IBAC can investigate. This means conduct that is unethical, improper, or abusive of power, but that does not rise to criminal conduct, falls outside IBAC’s jurisdiction.

A 2019 parliamentary inquiry found this definition too limiting, preventing IBAC from investigating “serious integrity breaches that would be investigated by anti‑corruption agencies elsewhere.” The Committee recommended broadening the definition to include “matters involving a serious disciplinary offence, misconduct worthy of termination or other relevant offences or instances considered in breach of public trust.” However, these reforms have not been implemented.

Moreover, IBAC’s jurisdiction over statutory authorities, such as the VLSB, remains ambiguous. While IBAC oversees “public officers,” the definition may not clearly capture regulators exercising statutory powers. This creates a gap where administrative abuse by regulatory agencies—perhaps the most consequential form of government overreach affecting ordinary citizens—may evade anti‑corruption scrutiny.

Flitner reportedly approached IBAC about his matter but received no redress. Whether this reflects jurisdictional limitations, resource constraints, or substantive judgment that no corruption occurred, the result is the same: a practitioner alleging systematic regulatory abuse found no avenue for independent investigation through Victoria’s premier anti‑corruption body.

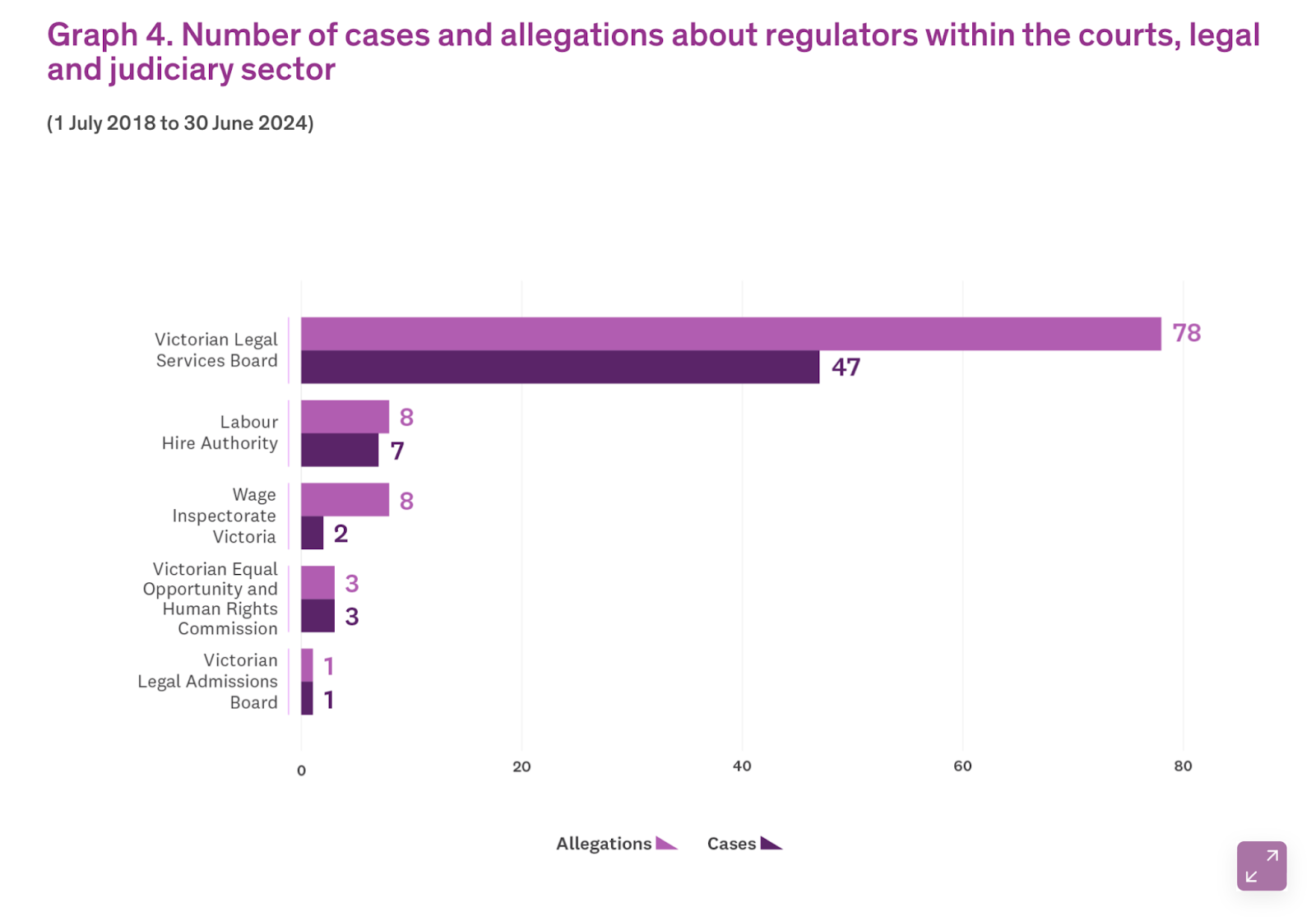

The VLSB consistently ranks at or near the top of the list of “regulators within the courts, legal and judicial sector” in terms of the number of misconduct and corruption complaints received each year by the Independent Broad-based Anti-corruption Commission (IBAC), and by a significant margin.

A snapshot of complaints received by IBAC for this sector in the financial year ending 30 June 2025 is provided below. These figures do not include complaints that IBAC rejects for lacking sufficient detail or for being otherwise inappropriate for its consideration.

IBAC’s own annually published statistics also consistently reveal a broad community view that:

- Corruption exists in Victoria and has a substantive impact on the performance of government functions; and

- The IBAC is ill-equipped to investigate, detect or prevent corruption or police misconduct.

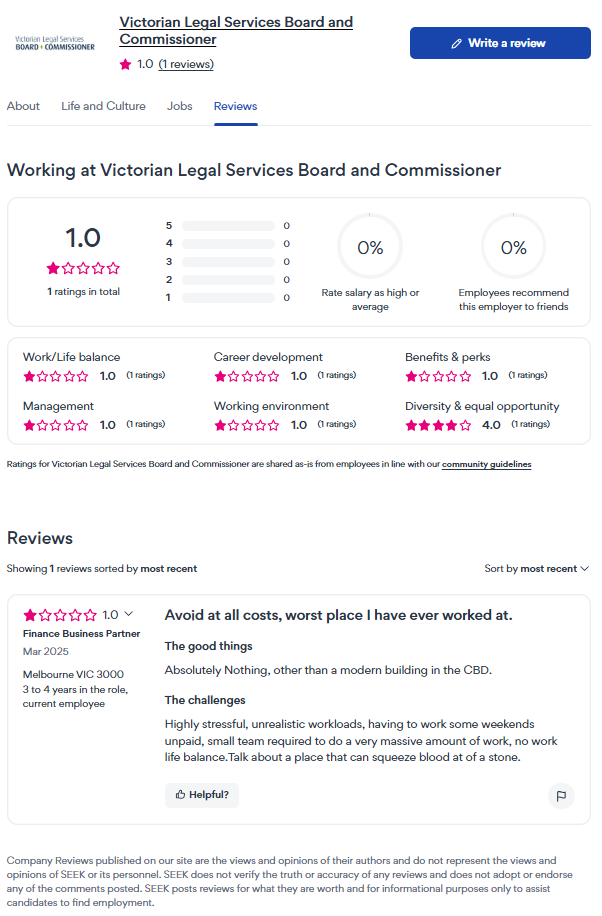

The VLSB’s Google reviews present a striking catalogue of people from diverse backgrounds and experiences, seemingly united only by their desire to vent visceral frustration and anger at the regulator.

Unsurprisingly, the VLSB’s ignominy is not confined to condemnation by lawyers and consumers of legal services. Its own staff do not appear to be enthusiastic supporters either, as suggested by the sole review posted on the organisation’s recruitment platform of choice, Seek.

Seek’s policy for accepting employer reviews requires it to verify that all reviewers are genuine employees of the organisation they review.

C. Parliament: Accountability Without Enforcement

The VLSB is nominally accountable to the Victorian Parliament through annual reporting requirements and ministerial oversight. The Attorney‑General must approve PPF expenditures and can determine minimum funding levels for legal aid. Parliamentary committees can summon VLSB officials, review performance, and recommend legislative changes. This structure creates formal accountability: a democratic institution overseeing an administrative agency.

In practice, however, parliamentary oversight of administrative agencies is episodic and politically contingent. Parliament’s attention is a scarce resource, allocated to issues that generate political salience through media coverage, constituent complaints, or advocacy campaigns. In the absence of such salience, agencies operate with considerable autonomy between annual reporting cycles. Parliamentary questions and committee hearings can yield useful information, but rarely lead to immediate remedial action in specific cases.

Our own reporting, based on sworn testimony from senior VLSB officials in proceedings before the Supreme Court of Victoria, shows that the VLSB operates with complete autonomy over disbursements from the $3.4 billion PPF, with no practical accountability or oversight.[xxiii]

Flitner reportedly approached Parliament but received no redress.

VII. Comparative Context: Patterns Across Jurisdictions

A. The Western Australia Law Practice Board

ABC reporting details serious allegations by Western Australian peak legal bodies that the Legal Practice Board of WA (LPBWA) has, over a sustained period, exercised its regulatory functions in ways that are procedurally deficient, excessively punitive, and systemically harmful to practitioners’ wellbeing and effective practice. These concerns have prompted a parliamentary inquiry into the Board’s governance and processes.

Core Systemic and Governance Concerns

The Law Society of WA’s profession‑wide survey identified a “detailed list” of complaints about the LPBWA’s governance and processes, including “delays, service challenges and problematic regulatory processes,” which the Society says have been building “for some time.”

Five peak bodies – the Law Society of WA, Community Legal WA, the Association of Corporate Counsel Australia, the Piddington Society and Women Lawyers WA – lodged a joint submission describing an “unprecedented loss of confidence” in the Board and calling for “urgent action.”

The submission alleges “chronic delays” across much of the Board’s work, “inappropriate and highly damaging investigation and prosecution processes,” and a pervasive “failure to engage, communicate and respond to enquiries and applications.”

In its 2023–24 annual report, the Board failed to meet key timeliness targets: only 42 per cent of “consumer matters” were resolved within 90 days (target 80 per cent), and only 40 per cent of complex investigations were completed within a year (target 80 per cent), with only internal review timeframes remaining on track.

Alleged Abusive or Harmful Disciplinary Practices

The peak bodies’ most trenchant criticisms are directed at the LPBWA’s disciplinary function, which they say has become “overly aggressive, persecutorial and punitive,” including suspending practitioners without a hearing or any finding of misconduct, and “expanding and escalating” complaints beyond their original scope.

The submission states that the Board’s conduct is “actively causing considerable harm,” with reported impacts ranging from exacerbated stress and pre‑existing mental health issues to “anxiety, depression, post‑traumatic stress disorder and suicidal thoughts,” and, at “the worst end of the spectrum,” the destruction of careers and practitioners’ lives.

Law Society members report a lack of procedural fairness in the Board’s dealings and say its communications have, in some instances, been “unprofessional, discourteous or overly aggressive,” heightening the sense of a persecutorial approach rather than a proportionate, protective one.

Alleged Failures of Communication, Transparency and Service

Practitioners describe the LPBWA as a “ghost organisation,” citing long delays in decisions, unanswered calls and emails, and the need for repeated follow‑ups simply to obtain a response.

The submissions include reports of mishandling sensitive information, including documents containing personal data being sent to the wrong lawyer and practitioners being required to prove they had already paid Board fees.

The Board itself acknowledges that its email accounts “were not consistently monitored,” leading to backlogs, lost emails, delayed responses and inconsistent inbox management across teams. It states that new systems have been implemented and that phone lines have been expanded from 2 to 20.

Financial and Cyber‑Governance Issues

The LPBWA was hacked in May 2025, forcing systems offline and requiring manual processing of practising certificate renewals. The Board says “limited corporate correspondence” was taken, including minimal contact information and bank account details for itself and a small number of third parties.

The Board’s most recent annual report shows financial reserves increasing from $11 million (June 2023) to more than $12.5 million (June 2024), prompting the Law Society to question whether practitioners funding the regulator through mandatory levies are receiving value for money and to ask why such accumulation is a “proper use” of those funds.

Board Responses and the Parliamentary Inquiry Context

These concerns led the WA Parliament’s Public Administration Committee to open an inquiry into “the operation and effectiveness” of the LPBWA, with the Committee Chair noting “a fairly high rate of dissatisfaction” in survey responses regarding timeliness, interaction, and the technical handling of applications.

In its submission, the Board accepts that “operational shortcomings” have occurred and that concerns have been raised about communication, timeliness, and complaint handling, but claims “significant progress has been made,” citing increased staffing in its Investigation and Legal team, recruitment efforts, and communication training.

The Board argues that its performance “ought not be measured by the feedback of those who feel aggrieved” but by “overall regulatory outcomes,” and characterises “isolated events or anecdotes of practitioner dissatisfaction” as insufficient grounds for structural reform.

While acknowledging it “needs to be aware that human beings are impacted by its decisions” and should be “appropriately responsive and accessible,” the Board insists there is “no utility in being ‘nice,’” presenting firmness – rather than procedural recalibration – as central to its public‑interest mandate.

Taken together, the ABC reports depict a regulator accused by its own peak stakeholders of entrenched delay, opaque and harsh disciplinary methods, poor communication, and questionable stewardship of practitioner‑funded reserves, culminating in an “unprecedented loss of confidence” and a parliamentary inquiry into whether its governance and processes remain compatible with access to justice and effective legal practice.

Notably, the allegations raised against the LPBWA are modest when compared with those made against the VLSB by numerous Victorian legal professionals and consumers in various forums, including court proceedings and before oversight bodies.

B. The National Pattern: Self‑Regulation’s Systemic Failures

An academic analysis of the regulation of the Australian legal profession identifies persistent failures that transcend individual jurisdictions. A comprehensive review published in the University of New South Wales Law Journal concluded that legal profession regulation has been “incapable of adopting a consumer‑oriented focus in its self‑regulatory disciplinary processes and codes of conduct, despite being urged to do so.” The traditional autonomous mechanisms of self‑regulation relied on by lawyers have proved inadequate for protecting the public interest:

Disciplinary processes focus on character rather than competence: The system investigates and prosecutes “gross breaches of duty” but ignores the vast majority of client complaints about “poor service—delay, incompetence, over‑charging and discourtesy or failure to communicate.” Until relatively recently, disciplinary authorities did not even investigate these kinds of complaints.

Scapegoating substitutes for systemic reform: Disciplinary proceedings readily result in individual practitioners being made scapegoats for character failings, rather than generating systemic reforms that address public concerns. Professional associations function simultaneously as unions and prosecutors for their members, creating structural conflicts of interest. In practice, this can result in individual practitioners being sacrificed during public scandals while the profession’s collective practices remain intact.

Consumer protection grafted onto an autonomous model: “More contemporary ‘responsive’ controls have merely been grafted onto the traditional model, and must now compete with it.” Consumer‑oriented reforms remain “weak, incomplete and overpowered by disciplinary and fiduciary controls.” Little attention has been paid to fostering genuine ethical responsiveness beyond a superficial consumerist veneer.

The national Legal Profession Reform Taskforce, established by the Council of Australian Governments, sought to address these problems through uniform legislation. The resulting Legal Profession Uniform Law—adopted by Victoria, New South Wales and Western Australia—was designed to simplify regulation, promote inter‑jurisdictional consistency and enhance consumer protection. However, structural uniformity does not remedy entrenched pathologies in regulatory culture. The Flitner and other cases suggest that the Uniform Law may, in fact, have exacerbated existing problems by standardising insufficient accountability mechanisms across multiple jurisdictions.

VIII. The Lawyer X Parallel: Institutional Corruption and Professional Betrayal

No examination of regulatory failure in Victoria’s legal profession is complete without acknowledging the Lawyer X scandal, widely regarded as the most serious breach of legal professional ethics in Australian history. Nicola Gobbo, a prominent criminal defence barrister, acted as a registered police informant from approximately 1993 until at least 2010, providing information about her own clients, their associates and others—potentially affecting 1,011 criminal convictions.

The High Court described Gobbo’s conduct as “fundamental and appalling breaches of [her] obligations as counsel to her clients and of [her] duties to the court.” More significantly, the Court held that “Victoria Police were guilty of reprehensible conduct in knowingly encouraging [Gobbo] to do as she did and were involved in sanctioning atrocious breaches of the sworn duty of every police officer.” The Royal Commission into the Management of Police Informants (RCMPI) concluded that Gobbo’s “breach of her obligations as a lawyer has undermined the administration of justice, compromised criminal convictions, damaged the standing of Victoria Police and the legal profession, and shaken public trust and confidence in Victoria’s criminal justice system.”

The VLSB’s response to Lawyer X is telling. The Board applied to the Supreme Court to remove Gobbo’s name from the roll of Victorian legal practitioners—a strike‑off application. This was an appropriate regulatory response: a lawyer who systematically betrayed clients over nearly two decades, causing catastrophic harm to the criminal justice system, should lose the right to practise. The application succeeded, and Gobbo was struck off.

But this raises an uncomfortable question: if the VLSB can identify and prosecute the most egregious ethical breach in Australian legal history, how did that breach continue undetected for seventeen years? Gobbo practised openly at the Victorian criminal bar throughout this period. She represented high‑profile clients in significant criminal proceedings. Police handlers contacted her repeatedly, creating documented records of information exchange. Yet no regulatory action occurred until media exposure forced the issue.

Moreover, the VLSB has taken no action against any of the lawyers who cooperated with Gobbo in the perversion of the course of justice, whether at the Office of Public Prosecutions, Victoria Police or within her own professional networks.

The contrast with Flitner is stark. Gobbo engaged in systematic, deliberate, prolonged betrayal of client confidentiality and professional duties, causing harm to hundreds of individuals and to the entire criminal justice system. She was eventually struck off through formal court proceedings. By contrast, Flitner faced comparatively minor disciplinary matters that he successfully appealed; the Court of Appeal found the initial sanction manifestly excessive. Yet his practice was seized without notice, transferred to another firm and destroyed—a penalty far more severe in practical effect than formal strike‑off, and imposed without any judicial process.

This disparity suggests regulatory priorities that sit uneasily with consumer‑protection rationales. The system failed to detect or prevent the most serious misconduct, but aggressively pursued relatively modest matters once the practitioner dared to appeal. One plausible explanation is that regulators react more harshly to challenges to their authority than to actual harm to clients. Gobbo’s misconduct, while catastrophic in retrospect, did not directly threaten the regulator’s institutional interests. Flitner’s successful appeal did.

IX. Theoretical Framework: Understanding Regulatory Pathology

A. The Self‑Regulation Paradox

Professional self‑regulation is justified by a core claim: that complex, specialised occupations require peer oversight because only practitioners possess the expertise to assess technical competence and ethical compliance. Lawyers contend that their work involves esoteric doctrine, context‑sensitive judgment calls, and duties to clients and courts that only other lawyers can properly evaluate. They argue that external regulation by non‑lawyers would lack the necessary sophistication and might endanger the professional independence lawyers need to challenge state power.

This argument has force. Legal practice does require specialised knowledge. Ethical questions frequently turn on fine distinctions: when does vigorous advocacy become misleading the court? When does confidentiality permit, or even require, disclosure? Non‑lawyers may well struggle with these nuances. Moreover, lawyer independence from government control serves crucial rule‑of‑law values: lawyers must be able to contest state action without fear of retaliation from government‑controlled regulators.

Yet self‑regulation generates an inherent conflict: the regulated community becomes the regulator. Professional bodies exist primarily to advance members’ interests—improving working conditions, maximising autonomy, shielding against competition, and protecting collective reputation. When these same bodies wield disciplinary powers, they must constantly reconcile competing imperatives: safeguarding the public versus safeguarding the profession, sanctioning wrongdoing versus preserving member solidarity.

Empirical research suggests this conflict often resolves in favour of professional interests. As Root Martinez and Juricic document,[xviii] lawyer disciplinary systems exhibit three core failings: sanctions do not effectively deter misconduct; lawyers do not fear bar authorities; and a lack of standardisation gives regulators wide discretion, which may make them hesitant to penalise colleagues. Lawyers are “unlikely to tattle on one’s friends or colleagues,” particularly in small jurisdictions where regulators must discipline people they know personally.

The result is what scholars describe as “responsive regulation without teeth”: elaborate procedural frameworks that simulate accountability while preserving professional autonomy in practice. When scandals demand visible action, the system tends to sacrifice individuals as scapegoats to protect the profession’s collective reputation, rather than pursuing structural reform.

This dynamic is evident in Victoria. Catastrophic failures such as Lawyer X went undetected for seventeen years, while comparatively modest matters have drawn disproportionately aggressive enforcement—particularly when the practitioner has dared to challenge regulatory authority.

B. Regulatory Capture and Institutional Self‑Protection

Classic regulatory capture theory, developed by economists George Stigler and Sam Peltzman, explains how regulatory agencies can come to serve the interests of the industries they oversee rather than the public. Mechanisms of capture include revolving doors (movement of personnel between regulators and industry); information asymmetry (regulators’ dependence on industry for expertise); cognitive capture (regulators internalising industry perspectives and assumptions); and resource constraints (agencies lacking the capacity to enforce rigorously).

Regulation of the legal profession displays several of these dynamics. The “transit of staff between regulator and regulated entities” creates personal and professional networks that blur the line between oversight and advocacy. Members of regulatory boards are often practitioners or academics whose future opportunities depend on maintaining professional goodwill. The VLSB’s practice of contracting private law firms to provide external intervention services also creates financial incentives for those firms to support, and benefit from, aggressive enforcement.

However, the Flitner case points to a distinct pathology: regulatory self‑protection. When a practitioner successfully challenges Board action in court or makes serious allegations against senior staff, the Board risks institutional embarrassment, potential liability for costs, and public doubts about its competence. Officials may perceive such challenges as threats to their professional standing and respond with retaliatory enforcement aimed at deterring future challenges. This is a form of regulatory self‑dealing: the agency uses its enforcement powers not to protect consumers, but to protect its own institutional interests.

The VLSB’s aggressive, costly and unlawful attempts to prevent publication of this article’s content, through multiple failed suppression applications, further reinforce this inference.[xix]

Crucially, this pathology differs from traditional capture, in which regulators advance the interests of the industry as a whole. Here, the regulator targets particular practitioners to protect its own power. The broader profession may nevertheless support such enforcement when it is directed at marginal members or perceived outsiders, thereby preserving the dominant group’s status. The VLSB’s apparent targeting of Flitner after his Court of Appeal victory, and the alleged targeting of NSW solicitors who reported misconduct by major institutions, fit this pattern: highly aggressive enforcement against practitioners who threaten entrenched power.

C. Administrative Law Theory and the Emergency Exception

Administrative law scholarship distinguishes between procedural and substantive review of government action. Procedural review asks whether the proper process was followed; substantive review examines the merits of the decision itself. Courts are far more willing to intervene on procedural grounds than on substantive ones, reflecting separation‑of‑powers concerns: judges should not substitute their policy judgments for those of politically accountable administrators, but they can and must ensure procedural regularity.

Procedural fairness serves multiple values beyond accuracy. It upholds human dignity by allowing affected persons to be heard before decisions that affect them are made. It promotes transparency and accountability by requiring administrators to articulate reasons and consider objections. It constrains arbitrary power by ensuring that decisions cannot be made in secret and without notice to affected parties. And it enhances legitimacy by giving stakeholders procedural participation even when substantive outcomes go against them.

The emergency‑powers doctrine recognises that exceptional circumstances may justify abbreviated procedures. When immediate action is necessary to prevent imminent harm, administrative agencies may act first and provide hearings later. But several safeguards limit this exception. Emergencies must be genuine, not manufactured. Emergency measures must be proportionate and time‑limited. Judicial review must remain available. And even emergency procedures must respect core due process values—there is no such thing as “zero process.”

On the facts presented, the Flitner intervention fails every test for legitimate emergency action. No evidence suggests imminent client harm requiring instant seizure without notice. The intervention was not temporary but permanent: the practice was immediately transferred and destroyed, not temporarily supervised pending resolution of concerns. Flitner was prevented from seeking judicial review before the seizure occurred. And absolutely no process was provided—not an abbreviated process, not a delayed process, but no process at all.

This represents, on one view, an instance of administrative‑law pathology: the normalisation of emergency powers for routine use. As scholars examining emergency legislation warn, the danger is that extraordinary powers, justified by exceptional circumstances, become tools of bureaucratic convenience, deployed “for the sake of convenience” rather than desperate necessity. When regulators can seize businesses without notice whenever convenient, emergency powers become ordinary powers, and the rule of law risks collapsing into rule by administrative fiat.

X. Systemic Implications and the Erosion of the Rule of Law

A. Access to Justice and Regulatory Deterrence

The destruction of small‑firm practices like Flitner’s has ripple effects throughout the justice system. Suburban solicitors serve middle‑income clients who cannot afford major CBD firms but need more than self‑representation or what legal aid can provide. These practitioners handle routine matters—wills, conveyancing, minor litigation, family law—that constitute most citizens’ primary interaction with the legal system. When regulatory enforcement drives such practitioners out of business, access to justice for the communities they serve is diminished.

The chilling effect on professional advocacy is equally significant. If lawyers believe that zealously representing clients against regulators invites retaliation, they will moderate their advocacy. If appealing unfavourable disciplinary decisions and making complaints against senior officials risks escalated enforcement, practitioners will accept unjust sanctions rather than exercise their rights. The Stephen Walters and Glenn Mohammed Postscript—detailing the consequences faced by lawyers for vigorously defending Flitner—epitomises this dynamic. When lawyers fear representing clients against perceived regulatory overreach, the entire system of checks and balances is undermined.

Regulatory deterrence should target harm to clients, not challenges to regulatory authority. A well‑designed system punishes professional misconduct proportionately while welcoming appeals of regulatory decisions as a quality‑control mechanism that improves accuracy and legitimacy. On the accounts considered here, the VLSB appears to operate on opposite principles: tolerating serious misconduct (as in the Lawyer X scandal, which went undetected for seventeen years) while aggressively targeting practitioners who successfully appeal. This inverted deterrence structure undermines the system’s legitimacy and its protective function.

B. The Public Purpose Fund as Private Subsidy

The financial architecture surrounding external interventions creates perverse incentives that can corrupt regulatory judgment. When the VLSB can appoint private contractors to lucrative manager positions, pay them from a multi‑billion‑dollar fund facing no independent oversight, and face limited accountability for cost overruns or wasteful expenditure, the incentive structure encourages rather than constrains aggressive intervention.

Private law firms like Thomson Geer have a strong financial incentive to accept external intervention appointments and to bill extensively once appointed. Unlike court‑appointed receivers who face judicial scrutiny of their fees, external managers appointed by the VLSB bill the Public Purpose Fund with comparatively little apparent oversight. If invoices are indeed “inflated or unjustified” as alleged, this represents a wealth transfer from the legal profession as a whole (reducing funds available for legal aid and public purposes) to politically connected contractors, mediated by a regulator facing no direct budgetary constraints.

The lack of standing for affected practices to challenge these charges compounds the problem. When the VLSB appoints a manager, the manager’s “client” is deemed to be the Board, not the practice being managed. This legal fiction prevents practices from exercising the normal client rights to review invoices, demand itemisation, and challenge unreasonable charges. The practice pays (indirectly, through reduced access to the PPF) but has no consumer protection.

This structure appears inconsistent with basic principles of financial accountability in public administration. Government spending should serve public purposes, not private enrichment. Expenditure decisions should be subject to budget constraints that incentivise cost‑consciousness. Affected parties should have standing to challenge wasteful spending. Based on the analysis presented, the PPF system fails to meet any of these requirements, creating a closed loop in which regulatory decisions, private contractors, and public funds operate in mutually reinforcing insularity.

C. Institutional Legitimacy and the Shadow of Corruption

The most corrosive effect of cases like Flitner’s is damage to institutional legitimacy. Legal systems depend on public confidence that law is applied fairly, consistently, and without favouritism or corruption. When regulators appear to target practitioners who challenge their authority, when oversight mechanisms fail to provide redress, and when billions of dollars are spent with limited transparency, public trust erodes.

The IBAC definition of corrupt conduct is instructive: conduct by public officers that involves a “relevant offence,” typically encompassing bribery, fraud, and abuse of office. The narrow focus on criminal conduct may miss equally destructive forms of corruption, such as regulatory capture, institutional self‑dealing, and the misuse of legitimate powers for illegitimate purposes. An administrator who accepts no bribes but systematically retaliates against critics may harm public administration as profoundly as one who embezzles funds.