I. Introduction

The authority of law in democratic systems depends substantially on a foundational assumption: that judicial decisions represent the inevitable logical consequence of prior legal rules applied to facts. Judicial opinions are architecturally constructed to reinforce this assumption, presenting conclusions as mathematically determinate outcomes of neutral legal application. As Justice Benjamin Cardozo candidly acknowledged, however, the lived experience of judicial decision-making bears little resemblance to this presentation. Cardozo famously described the judge’s search for certainty as futile, locating legal reasoning within a “trackless ocean” of ambiguity, competing interpretative schemas, and irresolvable doctrinal tensions.

The puzzle this observation presents is not merely academic. If the law is genuinely indeterminate—if legitimate arguments exist supporting contradictory conclusions—then the iron certainty radiating from judicial opinions becomes something other than a discovery of pre-existing truth. It becomes, necessarily, a construction. This raises questions that strike at the legitimacy of judicial authority itself: What psychological mechanisms convert opacity into apparent clarity? How does subjective judgment masquerade as objective analysis? And what are the systemic consequences when the institution charged with interpreting law operates, often unknowingly, through processes of narrative fabrication rather than legal deduction?

This report examines the cognitive architecture underlying these questions, focusing specifically on coherence bias as both an explanatory framework and a cautionary diagnosis of structural vulnerability in rule-of-law systems.

II. The Certainty Paradox in Judicial Discourse

A. The Rhetorical Construction of Inevitability

Judicial opinions employ a distinctive rhetorical strategy that naturalises contingency. Facts are presented in linear order, supporting conclusions that appear to follow with quasi-mathematical necessity. Rules are stated with precision; their applications to facts are presented as logical deductions. Alternative interpretations, when acknowledged at all, are systematically refuted. The cumulative effect transforms what Cardozo recognised as a fundamentally uncertain judgment into a document that appears to record inevitable conclusions.

This rhetorical architecture serves essential institutional functions. Citizens must believe the law constrains judicial power, or the legitimacy of judicial authority collapses. Legal professionals must maintain faith that doctrine is discoverable rather than invented, or the entire project of legal practice loses coherence. Judges themselves must experience their decisions as principled rather than arbitrary, or moral self-conception becomes impossible. The rhetorical presentation of certainty is thus not merely misleading; it is institutionally necessary and psychologically essential for judges themselves.

Yet the gap between this presentation and the actual decision-making process has widened as jurisprudence has become more sophisticated. We have long known that law is indeterminate in significant domains—that statutory language is ambiguous, that precedent conflicts, that constitutional principles compete, that doctrinal rules generate counterexamples. Legal scholarship across schools of jurisprudence accepts these premises. Yet judicial opinions continue to present decisions as though none of these indeterminacies exist.

B. The Ratzlaff Case as Paradigmatic Evidence

Ratzlaff v United States provides crystalline evidence of this paradox. The underlying facts were straightforward: Waldemar Ratzlaff purchased multiple cashier’s cheques, each just under $10,000, to avoid currency-reporting requirements triggered at the $10,000 threshold. He was prosecuted for “wilfully” structuring currency transactions to evade reporting obligations.

The central legal question was not novel or uniquely ambiguous: Did the statute require that Ratzlaff know that structuring itself was prohibited, or merely that he knew he was evading reporting requirements? This framing created what cognitive psychology terms a “dilemma set”: a constellation of genuinely competing interpretations, each supported by legitimate legal argument.

The volume and distribution of competing arguments at this juncture are worth highlighting. The justices faced approximately 30 distinct interpretative frameworks regarding congressional intent. Critically, “the pull of those arguments was split almost perfectly down the middle, 50–50,” an almost perfect equipoise of conflicting legitimate authority.

This is the state of genuine uncertainty: the kind Cardozo described, where legal reasoning has exhausted itself, and no objective method remains to resolve the contradiction. It is the trackless ocean in its fullest expression.

C. The Transformation: From Dilemma Set to Rhetorical Certainty

Yet in their final written opinions, the justices transformed this essential equipoise into perfect coherence. The majority opinion, which favoured acquittal, constructed a document containing 64 separate propositions. Remarkably, every single one supported their conclusion. There were no loose ends, no lingering doubts, no acknowledgement of the counterarguments’ force.

The dissenting justices, reviewing the identical facts and legal authority, constructed an equally coherent narrative. Their opinion contained 61 propositions, and every one supported a conviction—the opposite conclusion. Two perfectly coherent stories. Two internally flawless architectures. Two completely contradictory outcomes.

Nine of the nation’s most experienced and intelligent jurists, employing identical legal materials, produced two narratives of absolute internal consistency that were categorically opposed to each other. This is not a minor problem in legal reasoning. This is the certainty puzzle in its starkest form: evidence that the appearance of deterministic reasoning is constructed rather than discovered.

III. The Psychological Mechanism—Coherence Bias

A. Defining and Locating Coherence Bias

The psychological mechanism generating this transformation is coherence bias: the brain’s automatic, largely unconscious tendency to take conflicting or ambiguous information and reshape it into a coherent, internally consistent narrative. This is not a marginal feature of human cognition; it is fundamental to how minds operate. When confronted with complexity, ambiguity, or contradiction, the brain does not remain suspended in equipoise. It actively constructs meaning, integrating disparate information into unified interpretative schemas that feel true, solid, and determinate.

Coherence bias is not a bug in human reasoning; it is a feature. The capacity to convert chaos into narrative coherence is how humans navigate a complex world, make decisions, and avoid psychological paralysis. It is adaptive in most domains. Yet in domains where the appearance of objectivity is essential to institutional legitimacy, particularly adjudication, this same feature becomes a liability.

The process operates largely outside conscious awareness. By the time a judge reaches a decision, they are typically unaware of the extent to which their perception of the case has been shifted, refined, and selectively filtered by the coherence-building process. The judge does not consciously deceive. Rather, their mind has already performed the work of coherence construction, and the result feels clear, obvious, and inevitable.

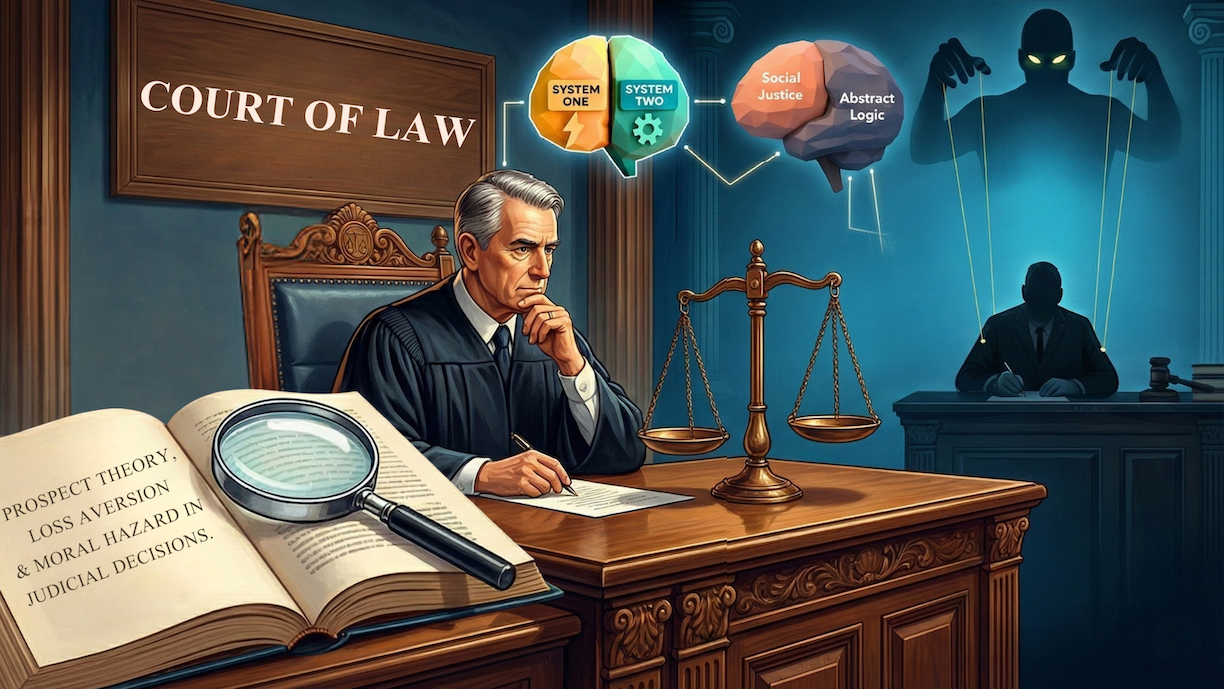

B. The Three Mechanisms of Coherence Construction

The coherence-building process operates through three primary techniques, all unconscious:

Gatekeeping

The first mechanism involves determining which facts, legal arguments, and precedential authorities even enter the narrative field. In Ratzlaff, the majority opinion omitted or minimised facts regarding Ratzlaff’s intentional deliberation and sophisticated structuring scheme that appear prominently in the dissent. These were not lies; they were gatekeeping decisions about what facts mattered to the story. The dissenting opinion emphasised Ratzlaff’s active scheming; the majority characterised him as more passive. Same defendant, same actions, different stories—generated through selective fact admission.

Bolstering

The second mechanism involves differential amplification of evidence. Some facts are highlighted and repeatedly reinforced; others are mentioned once or buried in footnotes. Some precedents are treated as controlling authority; others are distinguished and relegated to marginal significance. This is not conscious distortion but automatic emphasis and de-emphasis that creates the subjective experience of weight and importance.

Rule Selection

Legal interpretation is notoriously underconstrained by rules. Legal scholar Karl Llewellyn demonstrated that for virtually every interpretative canon in existence, an opposing canon of equivalent legitimacy exists. These he termed “thrust and parry.” Should a court adhere strictly to statutory language? Yes, says one rule. Should a court look past language to legislative purpose? Yes, says another rule of equal validity. The coherence engine selects the rule that fits the narrative already forming. This is not conscious dishonesty; it is unconscious rule-shopping in the service of coherence.

These three mechanisms—gatekeeping, bolstering, and rule selection—work in concert, largely outside judicial awareness, to convert the dilemma set into a coherent narrative that feels determinate.

C. The Psychological Experience of Certainty

The result of this coherence-building process is the famous “judicial hunch,” the moment a judge simply knows what the correct answer is, even if they cannot fully articulate how they reached it. This hunch is not mystical insight; it is the conscious experience of an unconscious cognitive process. Cardozo captured this perfectly in describing how “a solution seems to emerge from a fog of unconscious origins, slowly lighting up the path forward.” The feeling is genuine; the source is hidden.

By the time the opinion is written, the judge’s perception of the case has been so thoroughly reorganised by the coherence-building process that the opposite outcome seems literally unimaginable. The judge does not feel they are constructing a story; they think they are discovering truth. The coherence is so complete that it produces genuine conviction. This is not deception; it is a kind of cognitive self-deception in which the mind organises itself around a resolution and then loses access to the organising process itself.

IV. Implications for the Rule of Law

A. The Legitimacy Problem

These findings present an acute challenge to the legitimacy structures of common law systems. The rule of law rests on the premise that law constrains judicial discretion—that judges apply pre-existing law rather than create new law through wilful decision-making. This constraint is meant to distinguish judicial authority from arbitrary power.

Yet if the transformations documented in Ratzlaff are universal features of judicial cognition—if coherence bias operates as a fundamental mechanism in all complex judicial decisions—then the constraint is largely illusory. Judges are not discovering law; they are constructing law through unconscious cognitive processes designed to generate coherence rather than objective truth. The appearance of deterministic reasoning is precisely that: appearance.

This does not necessarily mean judicial decisions are unjust or that judges are corrupt. It means the institutional mechanisms for constraining judicial discretion are weaker than the rule-of-law theory assumes. Judges are not acting arbitrarily in the sense of randomly choosing outcomes. Rather, they are constrained by psychological coherence-building processes that generate determinate outcomes while remaining largely invisible to conscious oversight.

B. Democratic Accountability and Transparency

The opacity of these processes creates a problem of democratic accountability. Citizens in democracies need to understand how power is exercised to participate meaningfully in oversight. When judicial decision-making processes are largely unconscious, and when opinions are deliberately structured to obscure the contestability that characterises the decision-making process itself, democratic scrutiny becomes compromised.

The Ratzlaff example demonstrates this clearly. A citizen reading only the majority opinion would conclude that the law’s meaning was clear, that Congress’s intent was evident, and that Ratzlaff’s liability was inapplicable. Reading only the dissent, the citizen would reach the opposite conclusion. Neither opinion signals to readers that these were genuinely contestable judgments, supported by approximately equal weight of compelling authority. The rhetorical strategy of judicial opinions—presenting decisions as inevitable—systematically obscures the role of judicial discretion.

In democratic theory, discretionary power exercised by unelected officials is problematic in direct proportion to its magnitude and its opacity. To the extent that coherence bias generates significant discretionary outcomes that remain largely invisible in judicial opinions, this represents a democratic accountability deficit.

C. The Integrity of Legal Doctrine

These findings also challenge the pretence that legal doctrine operates as a genuine constraint on decision-making. If coherence bias allows judges to construct perfectly coherent narratives supporting contradictory conclusions from identical legal materials, then legal doctrine is not constraining decision-making; it is supplying the raw material for post hoc rationalisation.

This is not a new observation; Critical Legal Studies scholars identified this problem decades ago. But the cognitive-psychology framework clarifies that the problem is not individual judges’ dishonesty or ideological capture (though these may occur). Rather, it is a universal feature of how human minds process complex information in the face of ambiguity. Coherence bias does not distinguish among liberal and conservative judges, outcome-oriented and formalist judges, or highly able and mediocre judges. It operates across all judges, in all domains of doctrinal ambiguity.

D. Systemic Corruption and Rule-of-Law Vulnerability

The certainty puzzle also illuminates how coherence bias creates systemic vulnerability to corruption of rule-of-law institutions. While the mechanisms documented here are largely unconscious rather than deliberately corrupt, they create the cognitive preconditions for deliberate corruption to operate effectively.

Consider: if judges have access to multiple legitimate interpretative rules, and if coherence bias allows them to construct perfect narratives supporting any outcome, sophisticated institutional corruption need not involve overt coordination or bribery. Instead, it might operate through systemic influences on the premises from which coherence-building begins.

For example, if—through budgetary leverage, nomination processes, or social pressure—powerful interests can influence which facts, precedents, or interpretative canons gain salience in judicial consciousness before the coherence-building process begins, then the coherence engine will convert those influenced premises into perfectly coherent narratives supporting desired outcomes. The judge remains honest; the process remains unconscious; yet the result has been systematically influenced.

This is likely how modern corruption of legal institutions often operates: not through crude bribery but through subtle influence on the information environment from which judicial cognition operates. Coherence bias ensures that once influenced premises have been accepted into the initial frame, the judge’s own mind will construct coherence around those premises, reaching determinate conclusions that feel obvious and inevitable.

V. Deeper Implications—Truth, Certainty, and Institutional Design

A. The Epistemological Problem

The most unsettling implication of the certainty puzzle concerns epistemology itself. Cardozo’s observation—that the feeling of being right is not discovered in law books but created by the hidden workings of judges’ minds—suggests that certainty may be a psychological construction rather than an objective feature of the world.

Suppose nine of the nation’s best legal minds examine identical facts and law and produce two equally coherent yet contradictory narratives, both generated through the same coherence-building mechanisms. What does it mean to have “found the right answer”? The mechanisms are identical; the outputs are opposite. This suggests that rightness is not objective in the way rule-of-law theory assumes.

More broadly, this raises questions that extend far beyond the law. If human cognition systematically converts uncertainty into the subjective experience of certainty through unconscious coherence-building, how much of what we experience as objective truth is actually psychologically constructed? To what extent are our most deeply held convictions—in law, in politics, in empirical domains—products of coherence bias rather than discoveries of objective reality?

B. Institutional Responses: The Transparency Imperative

These findings suggest that legitimacy in rule-of-law institutions requires a radical transparency initiative. Currently, judicial opinions conceal the contestability of legal questions and the discretionary character of interpretative choices. They present decisions as inevitable rather than contingent.

One reform would require judicial opinions to explicitly document the dilemma set—the competing interpretative possibilities—and explain why specific options were selected over others. Rather than presenting one set of propositions as obviously superior, opinions might candidly acknowledge that multiple coherent narratives were available and explain the judge’s reasoning for choosing one.

This would increase institutional transparency and create accountability mechanisms for examining whether discretionary choices reflect systemically biased premises. It would also reduce citizens’ false confidence in the objective determinacy of law, creating more realistic expectations about what judicial institutions can actually deliver.

Alternatively, institutional reforms might focus on deliberate cognitive diversity in decision-making. Multijudge panels create some protection against individual coherence bias, but research suggests panels can reinforce rather than mitigate biased reasoning through group-polarisation effects. More radical alternatives, such as mandatory adversarial brief-writing from multiple coherent positions, or systematic exposure to the best arguments for competing conclusions before coherence-building begins, might partially offset the effects of bias.

C. The Deeper Question

Yet beneath these practical reform proposals lies a more fundamental question. If coherence bias is universal and largely unconscious, and if it generates the feeling of certainty that makes judicial authority psychologically tolerable to judges, then reducing it entirely might make judicial office existentially unbearable. Judges might become paralysed by awareness of the contingency of their choices.

This points to a tragic element in rule-of-law governance. The feeling of certainty that legitimises judicial authority may depend partly on the very unconsciousness that undermines actual rule-of-law governance. A perfectly transparent judicial process might sacrifice legitimacy in pursuit of truth. A judiciary that fully recognised the contingency of its decisions might lose the psychological confidence necessary to decide cases at all.

This is not an argument against transparency. Rather, it is an acknowledgment that some of the tensions in rule-of-law governance may be irreducible and require institutional compromise rather than complete resolution.

VI. Conclusion

The certainty puzzle reveals a fundamental discontinuity between how judicial decision-making actually operates and how it is presented in judicial discourse. The transformation from the trackless ocean of genuine legal uncertainty to the rock-solid ground of judicial certainty is not a discovery of pre-existing truth. It is a construction—an unconscious cognitive process in which the mind builds coherence from contradiction, certainty from ambiguity, and inevitability from contingency.

This process operates through gatekeeping (controlling which information enters the narrative), bolstering (differentially amplifying evidence), and rule selection (choosing among competing interpretative canons). None of these occurs consciously. Rather, judges experience their decisions as obvious and inevitable because the coherence-building process has been completed before conscious reflection begins.

The implications are profound. First, they suggest that coherence bias generates significant judicial discretion in domains of genuine legal indeterminacy, undermining the rule-of-law assumption that law constrains judicial power. Second, they illuminate how systemic influences on judicial premises, operating before coherence-building begins, can systematically bias outcomes without requiring conscious conspiracy or individual dishonesty. Third, they suggest that the subjective feeling of certainty may be a psychological construction rather than an objective feature of legal reality.

For sophisticated observers—legal professionals, academics, and engaged citizens—these findings demand a more realistic understanding of what judicial institutions actually do. Courts do not mechanically apply law; they exercise discretion constrained by psychological coherence-building rather than by objective legal rules. This is not an indictment of judges, who generally operate with integrity and good faith. Rather, it is a recognition that the psychological architecture of human cognition, while enabling judges to reach determinate decisions, does so through mechanisms largely invisible to institutional oversight.

The solution is not to eliminate coherence bias, which would require changing the fundamental architecture of human cognition. Instead, it is to increase institutional transparency about how judicial discretion actually operates, to build accountability mechanisms that acknowledge this discretion, and to calibrate expectations about rule-of-law governance to align with these psychological realities. Democracy depends on citizens’ understanding of how power is exercised. The certainty puzzle suggests we have been systematically misunderstanding a fundamental source of legal authority. Transparency and realistic expectations about judicial cognition are prerequisites for institutions that can actually constrain power, rather than merely appearing to do so.