I. Introduction

The modern justice system is built on a foundational promise: judges apply the law objectively, mechanically, and inevitably. When a court delivers a verdict, the entire performative apparatus—the courtroom ritual, the formal opinion, the invocation of precedent and logic—is designed to project absolute certainty and inevitability. The law is presented as a deductive machine: feed in facts, apply logic, and the outcome is revealed as an objective truth. This narrative serves critical legitimacy functions, creating public confidence that judicial outcomes derive from neutral legal principles rather than personal caprice or power.

Yet this idealised conception of judicial reasoning has faced sustained scholarly challenge for nearly a century. Jurists like Benjamin Cardozo and Jerome Frank argued that formal legal opinions were often post hoc rationalisations for decisions reached through less systematic mental processes. More recently, empirical research in cognitive psychology has begun to illuminate how judicial minds actually operate, and the findings are sobering. Judges’ mental processes are not deductive machines but rather complex networks of constraint satisfaction, subconscious biasing, and emotional influence.

This article examines what we term the “psychological paradox” of modern adjudication: the systematic gap between the formal appearance of certainty and the cognitive mechanisms that generate judicial decisions. We argue that understanding this paradox is essential for addressing systemic corruption because the cognitive vulnerabilities inherent in judicial reasoning create structural openings through which corruption, both traditional and contemporary, can infiltrate and compromise the rule of law.

II. The Formal Architecture vs Cognitive Reality: The Impossibility of Radical Neutrality

Legal opinions must present themselves in what Karl Llewellyn termed “the garb of certainty”. As the sources note, a judge cannot publish an opinion stating, “I was 51% sure on this one”. The institutional requirement for finality and authoritative closure demands that judges present singular, confident answers even when faced with genuinely ambiguous precedents, conflicting statutory language, and irreconcilable policy arguments.

This institutional demand confronts a fundamental cognitive reality: the initial inputs to judicial reasoning are typically contradictory. A single case may involve competing precedents, ambiguous legislative history, conflicting expert testimony, and policy rationales that legitimately support opposite conclusions. The raw material of legal reasoning is contradiction and uncertainty.

The critical question becomes: How does the judicial mind transform this contradictory input into the confident, unified output that the legal system demands?

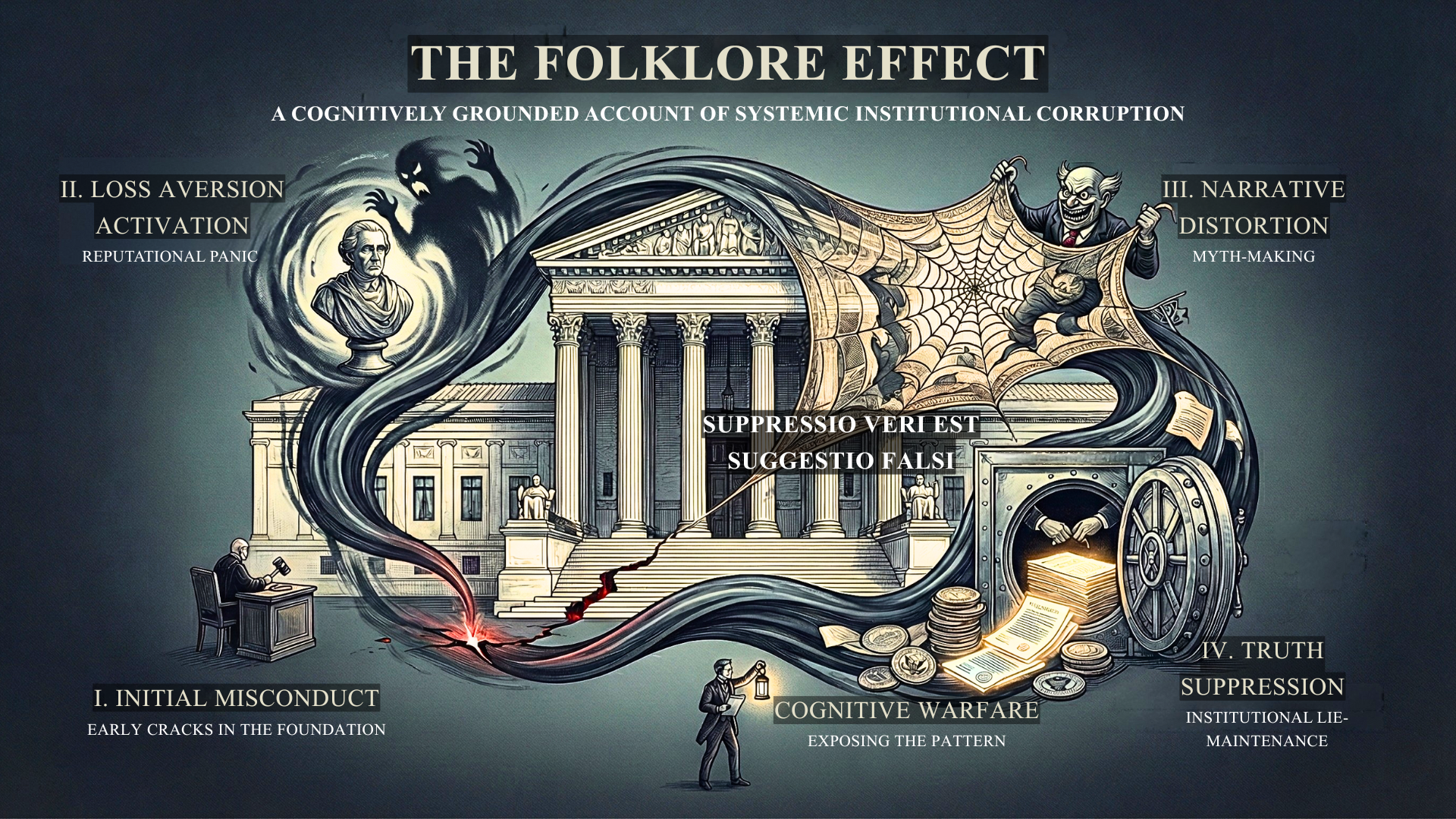

A. Constraint Satisfaction: The Subconscious Architecture of Judicial Reasoning

Contemporary cognitive science suggests that judicial reasoning does not operate through conscious, linear, logical deduction. Instead, the sources describe a process called constraint satisfaction, a fundamentally different mechanism.

In this model, all elements of a case—facts, precedents, legal principles, and policy considerations—exist as nodes in a vast interconnected network in the judge’s mind. The relationships between these elements function as “constraints”: if two elements support each other, they are connected by excitatory (positive) links; if they contradict each other, they are connected by inhibitory (negative) links.

The judicial mind does not consciously resolve these conflicts through formal logical analysis. Instead, the network undergoes repeated cycles of activation, like waves washing across it, seeking the configuration that maximises overall satisfaction and minimises internal contradiction. Elements receiving strong support from their neighbours become stronger and more salient. Elements that are consistently contradicted or suppressed degrade and fade away from conscious consideration.

This process is largely subconscious. The judge experiences the outcome—a confident conviction about the correct legal answer—but does not directly perceive the underlying mechanism that generated it. The cognitive system efficiently produces a coherent mental model by actively suppressing competing models that may be nearly as coherent.

B. The Suppressed Counterargument

Here lies the critical, often overlooked implication: when a judge reaches a confident decision through constraint satisfaction, the opposing arguments are not refuted by logical demonstration. Instead, they are actively suppressed to achieve cognitive closure.

The research examined in the sources reveals a startling reality: the suppressed model—the fully developed set of arguments for the losing side—is often no less coherent than the winning model. The judge’s opinion conveys extreme certainty, presenting the outcome as inevitable and foreordained. Yet within the judge’s own mind, there existed a near-perfect counterargument that was simply suppressed to achieve the feeling of cognitive closure.

This is not conscious dishonesty or deliberate distortion. It is the natural operation of a cognitive system that prioritises coherence and closure over the representation of genuine uncertainty and equipoise. The process fundamentally shifts the character of judging from “finding the law” to “structuring the law”, from discovering pre-existing legal truth to constructing coherence from genuinely ambiguous materials.

The Ratzlaff opinion discussed in the source material exemplifies this phenomenon. The case involved complex questions of legislative intent regarding specialised knowledge requirements. The justices generated 23 distinct arguments, which mapped onto eight different inference paths, with three pairs of those paths being directly contradictory. Neither possible conclusion—whether specialised knowledge was required or regular knowledge sufficed—was naturally supported by a coherent subset of arguments. The judge’s mind did not discover coherence; it imposed it, through the mechanism of constraint satisfaction, selectively strengthening one configuration over another.

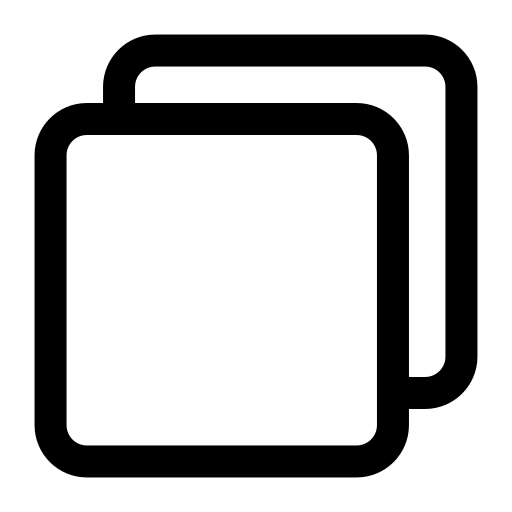

III. Systematic Cognitive Biases in Judicial Decision-Making

While constraint satisfaction describes the fundamental architecture of judicial reasoning, an equally troubling body of research documents that judges are susceptible to the same systematic cognitive biases that affect all human beings. These are not failures of individual character or intelligence. They are features of evolved human cognition that operate primarily outside conscious awareness and control.

A. The Anchoring Effect and Monetary Awards

One particularly well-documented bias is anchoring, the phenomenon whereby an initial number, even if explicitly irrelevant to the decision at hand, unconsciously influences subsequent judgments.

In a trial simulation study described in the sources, judges were given a case and exposed to a meritless motion to dismiss based on a low jurisdictional minimum of $75,000. The judges correctly denied the motion. Yet those judges who had simply been exposed to that arbitrary $75,000 number subsequently awarded significantly lower damages, nearly 30% lower on average. The median award for judges exposed to the anchor was approximately $882,000, compared to $1 million for the control group, which never saw the motion. An irrelevant low number had pulled down a nearly million-dollar judgment by almost a third.

This is particularly troubling because it reveals that the anchoring effect operates even on sophisticated, legally trained minds who consciously knew the anchor was legally irrelevant. The bias appears to operate subconsciously, below the threshold of conscious deliberation. A judge cannot avoid anchoring simply by learning about it or trying harder to ignore it.

B. Hindsight Bias and the Illusion of Inevitability

A second powerful bias documented in the sources is hindsight bias, the “I knew it all along” effect, whereby people systematically overestimate how predictable an event was before it occurred.

For judges, this bias is particularly pernicious because judicial review frequently involves assessing whether an outcome was predictable based on information available before the event. Yet judges, like laypeople, consistently struggle with this task.

In one study, judges were told the outcome of an appeal and then asked to estimate the ex ante likelihood of that outcome—that is, how predictable it was before they knew the result. The judges significantly overestimated the predictability of the outcome they had been told.

The truly revealing detail is this: when the percentages of judges who predicted outcome A were added across all judges who were told outcome A was the result, and similarly for all judges who were told outcome B was the result, the aggregate percentages summed to 172%. Mathematically, perfect, unbiased predictions would equal 100%. The 172% aggregate shows that judges who were told outcome A occurred retroactively believed A was highly predictable, and those told outcome B occurred retroactively believed B was highly predictable. The past always feels determined and inevitable, even when the original moment of decision was genuinely uncertain.

This bias has direct implications for how appellate judges assess trial court decisions and how they evaluate whether precedent required or merely permitted a particular outcome. The hindsight-biased judge systematically overestimates how much prior law constrained the decision, making past decisions appear more inevitable than they actually were, and thus more certainly correct.

C. Emotional and Demographic Influence

The “Thug” versus the “Student” Perhaps most directly relevant to concerns about discrimination and arbitrary decision-making is evidence that judges’ personal reactions to the litigants themselves measurably influence their decisions.

In an experiment examining challenges to strip-search procedures, researchers presented identical underlying facts and legal posture but varied only the description of the plaintiff. When the plaintiff was described as a “student”, 84% of judges granted summary judgment. When identical facts were presented, but the plaintiff was described as a “thug”, only 50% of judges granted summary judgment.

The difference represents a complete reversal of judgment, based essentially solely on demographic characterisation and the emotional or intuitive reaction it provokes. This reveals that decisions can be significantly swayed by the judge’s subjective feelings toward the litigants, whom they empathise with and whom they regard with suspicion.

D. The Persistence of Inadmissible Evidence

While judges are rigorously trained to exclude inadmissible evidence, research consistently demonstrates that such evidence measurably influences judicial decisions even when judges consciously attempt to disregard it. Prior criminal convictions, confidential settlement demands, and other information that judges have been explicitly instructed to disregard still seep into their decision-making, affecting both sentencing and damages awards.

This reveals a fundamental limit to conscious willpower and deliberate exclusion. A judge cannot simply choose not to process information that has entered consciousness, even with a deliberate intention to disregard it. The cognitive system processes information largely automatically, and this automatic processing influences subsequent judgments regardless of conscious intent.

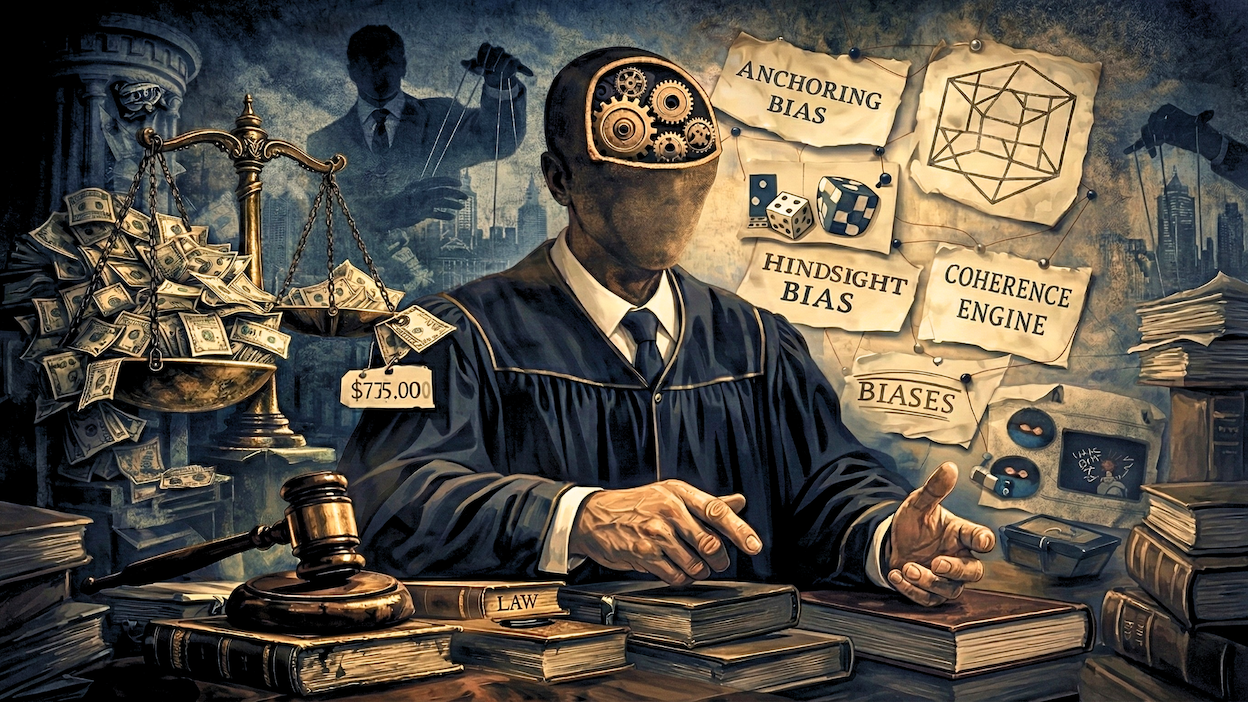

IV. Cognitive Vulnerabilities and Systemic Corruption: Defining Corruption as Integrity Failure

The sources suggest understanding corruption in society not merely as illegal payments changing hands—the conventional legalistic definition—but more fundamentally as the violation of impartiality principles and non-discrimination norms for personal or group advantage. Understood this way, corruption is a macro-level manifestation of failures in objective, non-personalised decision-making.

Widespread corruption has been empirically demonstrated to undermine economic development, reduce GDP, and destabilise institutions. These harms flow from the fundamental violation of the rule of law—the principle that decisions should be made according to general, impersonal rules rather than the personal preferences or interests of decision-makers.

A. The Structural Opening for Corruption

The cognitive mechanisms we have outlined—constraint satisfaction, anchoring, hindsight bias, and emotional influence—create structural openings through which corruption can infiltrate judicial systems.

Consider a judge facing a case with genuinely ambiguous legal materials. The constraint satisfaction mechanism will eventually produce a confident decision, but the outcome depends partly on which arguments and facts the system privileges. A judicial officer seeking to influence the outcome could do so through subtle manipulation of which arguments receive attention, which evidence is emphasised, or which framing considerations are foregrounded. The judge’s conscious mind may experience this as simply “finding the right answer”, when in reality the decision-making mechanism was influenced by elements below conscious awareness.

Similarly, the demonstrated susceptibility to anchoring, emotional reactions, and inadmissible evidence suggests vectors through which corruption could operate. A corrupted system might feed “anchors” into cases—specific monetary figures or damaging information—designed to unconsciously influence judicial outcomes.

More fundamentally, if judicial decision-making is not the deductive, inevitable process it appears to be, then the appearance of impartiality becomes crucial. When the mechanism actually determining outcomes involves subjective judgment and suppressed counterarguments, formal procedural safeguards designed to prevent bias become essential.

B. The Cognitive Warfare Dimension

The sources introduce the concept of cognitive warfare, defined as deliberate offensive manoeuvres aimed at influencing beliefs and behaviour by directly targeting the human mind. These attacks are typically synchronised across multiple channels and deliberately manipulate emotional and subconscious processes—the System 1 mechanisms we have discussed.

What makes cognitive warfare particularly threatening is that it deliberately exploits the cognitive vulnerabilities that affect human beings at scale. The same anchoring bias that influences individual judges, the same hindsight bias, the same susceptibility to emotional framing—these can be weaponised on a mass scale through coordinated disinformation, emotional appeals, and systematic manipulation of information environments.

In a society whose rule of law depends on impartial judicial systems, the deliberate weaponisation of cognitive vulnerabilities represents a threat that operates below the level of conscious awareness and exceeds the defensive capacity of System 2 conscious deliberation. A judge influenced by a coordinated cognitive warfare campaign—designed to poison information environments, activate emotional reactions, and prime particular decision frameworks—may be entirely unaware that their supposedly independent reasoning has been subtly channelled.

V. Institutional Safeguards and Their Limitations: Written Reasoning as Cognitive Discipline

One potential institutional check on cognitive bias is the requirement that judges provide written explanations for their decisions. The act of articulating reasoning in writing may force judges out of rapid, intuitive System 1 thinking and induce more careful System 2 deliberation. The judge must construct a narrative that is coherent and defensible to external scrutiny, not merely internally compelling.

This requirement serves two functions: it may induce the judge to slow down and verify that their implicit reasoning actually holds together logically, and it creates a transparent record that can be scrutinised for bias by appellate courts and the public.

However, this safeguard has significant limitations. First, the written reasoning is itself generated primarily by the exact constraint satisfaction mechanism that produced the decision. In that case, the opinion may amount to a post hoc rationalisation rather than an independent verification. Second, written opinions are structured with the conclusion in mind, which may bias the presentation of the reasoning process.

A. Recusal and Disqualification Rules

A second category of institutional safeguard involves rules requiring judicial disqualification when actual bias exists or when the appearance of bias might reasonably undermine public confidence. These rules aim to address both conscious bias and its appearance.

However, the cognitive science reviewed in the sources suggests that these rules face a fundamental problem: many relevant biases operate entirely below conscious awareness. A judge cannot reliably detect that their reasoning has been influenced by an emotionally valenced characterisation of a litigant, by an irrelevant anchor, or by inadmissible evidence. If the bias is genuinely subconscious, then a judge’s good-faith effort to detect their own bias may be ineffective.

This creates a case for understanding recusal rules not merely as responses to judicially detected bias but as necessary prophylactic measures to preserve the appearance of impartiality, which is itself essential to the legitimacy of the rule of law. If the judge cannot reliably know whether their reasoning has been contaminated, then stepping away when the appearance of bias exists may be the only viable institutional safeguard.

B. The Sufficiency Problem

More fundamentally, the analysis of constraint satisfaction and cognitive bias suggests that procedural safeguards focused on controlling decision-making within a case may be insufficient to address the deeper structural problem. The problem is not merely that individual decisions are sometimes biased; it is that the cognitive mechanism generating judicial decisions inherently prioritises coherence and closure over the representation of genuine uncertainty.

The sources note that the entire legal curriculum effectively trains future lawyers to impose coherence over conflict and to replace doubt with confidence. This becomes ingrained as a habit of mind for the legal profession. If this is the fundamental training that legal institutions provide, then procedural safeguards may operate at the margins of a more profound institutional logic.

VI. Educational and Institutional Reform: The Paradox of Legal Education

The sources raise a critical question: if the constraint satisfaction mechanism inherently suppresses competing arguments to achieve closure, and if legal education trains future lawyers to impose coherence and replace doubt with confidence, then the legal profession is systematically cultivating a habit of mind that may be fundamentally misaligned with the genuine complexity of human experience and social conflicts.

The entire casebook method, which forms the foundation of legal education, involves reading judicial opinions as exemplars of reasoning. But if these opinions are post hoc narratives that suppress nearly equally valid counterarguments, then the casebook method trains students to see false certainty as inevitable. It teaches them to impose coherence where genuine ambiguity exists.

This creates a profession whose fundamental mental habit is to construct false certainty, which then becomes embedded in judicial reasoning, legal opinions, and the advice lawyers give to clients. The cascade of false certainty begins in law school.

A. Reconceiving Legal Education

The sources pose a fundamental challenge: what changes might legal education need to embrace to cultivate the opposite quality—a genuine capacity to contend with openness to conflict and legal ambiguity, a trait that understanding the complexity of human experience seems to require?

Such a reorientation might involve:

Explicit engagement with the psychology of judging

Rather than treating legal reasoning as mechanical deduction, legal education could explicitly teach students about constraint satisfaction, cognitive bias, and the psychological mechanisms that actually generate judicial decisions. This would include training in recognising personal biases and explicit exercises in perspective-taking and in considering suppressed counterarguments.

Inversion of the casebook method

Rather than reading cases as examples of inevitable reasoning, students could be taught to identify the suppressed argument—the nearly equally coherent position that was sacrificed to achieve closure. This would train the mental habit of genuinely considering opposing positions rather than suppressing them.

Cultivation of epistemic humility

Legal education could systematically cultivate an understanding that even sophisticated legal reasoning often involves judgment calls in which genuine ambiguity persists. Rather than training confidence to displace doubt, it could train explicit recognition and articulation of uncertainty where it genuinely exists.

Deliberative practice and structured controversy

Students could engage in deliberative exercises specifically designed to maintain engagement with opposing arguments without cognitive collapse into a single position. This would train mental flexibility and the capacity to articulate genuine tensions rather than false resolutions.

B. Institutional Structural Reform

Beyond educational reform, institutional structures might be modified to better acknowledge and accommodate the genuine complexity that legal reasoning involves:

Plurality of decision-making perspectives

Rather than single-judge decision-making, appellate and significant trial decisions benefit from multi-judge panels and deliberative processes that institutionalise the consideration of competing frameworks rather than their cognitive suppression.

Transparency about uncertainty

Judges should be encouraged to acknowledge genuine uncertainty or equipoise in their reasoning rather than presenting false certainty. This would require changing institutional expectations and professional culture.

Systematic attention to the appearance of bias

Institutions could implement more robust procedures for identifying and addressing bias, recognising that subconscious biases cannot be reliably self-detected by judges.

Cognitive diversity in judicial selection

Judicial selection processes could more deliberately seek diversity in judges’ cognitive styles, life experiences, and perspectives, recognising that cognitive diversity may serve as a partial check on the constraints and biases that individual judicial minds bring to decision-making.

VII. Implications for the Rule of Law and Democratic Legitimacy: The Fundamental Legitimacy Challenge

The analysis presented in this article reveals a fundamental tension at the heart of modern judicial systems. The rule of law depends on citizens’ confidence that judicial decisions derive from the neutral application of impersonal rules. Yet the cognitive mechanisms actually generating judicial decisions are neither mechanical nor purely rule-governed. They involve subconscious processes, systematic biases, and emotional influences that operate partly outside conscious awareness or deliberate control.

The formal apparatus of judicial decision-making—the ritual, the written opinion, the invocation of precedent and logic—is designed to project certainty and inevitability. But this appearance is, in essential respects, a psychological illusion. The actual cognitive process is messier, more contingent, and less determinate than the formal presentation suggests.

This creates a potential legitimacy crisis. To the extent that citizens (or sophisticated observers, including judges themselves) become aware that judicial reasoning is not the mechanical process it purports to be, confidence in the rule of law may erode. The apparent certainty that provides legitimacy is revealed as partly performative.

A. Rule of Law Requires Acknowledging Limits

Paradoxically, a more robust long-term defence of the rule of law may require greater candour about the cognitive limits of judicial reasoning. Rather than defending an increasingly implausible claim of mechanical certainty, rule-of-law institutions may better serve themselves by acknowledging the genuine complexity of legal reasoning while implementing safeguards specifically designed to address the cognitive and institutional vulnerabilities this complexity reveals.

This would involve:

- Explicit commitment to procedural fairness and to institutional checks on cognitive bias, recognising that these are not merely formal requirements but essential to the legitimacy of the rule of law.

- Transparency about decision-making processes rather than mystification, allowing external scrutiny and deliberation about whether outcomes reflect genuine legal reasoning or cognitive shortcuts.

- Cultivation of cultural and educational norms that value intellectual humility, genuine consideration of opposing positions, and explicit acknowledgment of uncertainty where it exists, rather than the current legal culture of performative certainty.

- Explicit confrontation with cognitive warfare and information manipulation, recognising that the deliberate weaponisation of cognitive vulnerabilities represents a contemporary threat to the rule of law that requires an active institutional response.

VIII. Conclusion

A psychological investigation into judicial decision-making reveals a system far more complex than the mechanical deductive model that provides the conventional justification for judicial authority. Judges employ subconscious constraint satisfaction to achieve cognitive closure even in cases of genuine legal ambiguity. They are susceptible to systematic biases—anchoring, hindsight bias, and emotional influence—that operate primarily outside conscious awareness. They absorb and are influenced by inadmissible evidence despite a deliberate intention to disregard it.

These are not failures of individual judges or products of moral frailty. They are features of human cognition that all judges, however brilliant or well-intentioned, must confront. The cognitive mechanisms that ensure decisiveness and coherence in judicial reasoning also create vulnerabilities through which bias, corruption, and the manipulation of cognitive systems can infiltrate.

The current institutional response—written opinions, recusal rules, and procedural safeguards—addresses the symptoms but not the fundamental structure. A more adequate response requires:

- Explicit recognition in legal education and professional culture that judicial reasoning involves genuine judgment about genuinely ambiguous materials, not mechanical application of determinate rules.

- Institutional structures that embed consideration of competing perspectives and legitimate uncertainty, rather than encouraging their cognitive suppression.

- Deliberate safeguards against both actual bias and the appearance of bias, recognising that judges cannot reliably self-detect subconscious cognitive influences.

- Explicit confrontation with cognitive warfare as a contemporary threat to the rule of law, demanding an active institutional response.

- Cultural and professional norms that value intellectual humility and genuine engagement with complexity rather than performative certainty.

Most fundamentally, the rule of law is served not by maintaining an increasingly implausible illusion of mechanical certainty but by acknowledging the actual nature of judicial reasoning and designing institutions that protect against the vulnerabilities inherent in that reasoning. A legal system that recognises the constraints and biases of human cognition, and implements safeguards specifically responsive to those constraints, may ultimately provide more robust protection for the rule of law than one that rests on the pretence of mechanical inevitability.

The psychology of judging illuminates not a crisis of individual judicial integrity but a crisis of institutional design—and therefore an opportunity for genuine reform.